The title of this blog refers to the fact that this is a second attempt at writing about the killer influenza pandemic and how it impacted on cinema in Ireland in 1918-19. In October 2018, I started a blog about flu, but I never finished it. So this is the second wave of my research, prompted by 2020’s COVID-19 pandemic and an invitation to contribute to a webinar panel on the flu pandemic organized by members of HoMER, a network of researchers studying cinema history. Of course, I have been regretting now that I didn’t pursue that earlier piece to research to conclusions; several things conspired against it, including a lack of sources, because the issues of Irish Limelight, Ireland’s only cinema magazine of the time, are not extant, and the usually informative “Irish Notes” column in the London-based Bioscope did not appear often during the height of the pandemic.

As well as this, it looked two years ago like Irish cinema as a whole continued largely unchanged by the pandemic, despite cinema closures in some places. Many cinemas already dealing with the hardships of World War I, remained open despite the deaths in the community around them, from which they drew both their audiences and their staff. In a way, I think that this business as usual now looks stranger and more worthy of attention than it did two years ago because of the changed perspective that has come as the world experiences another pandemic a century later.

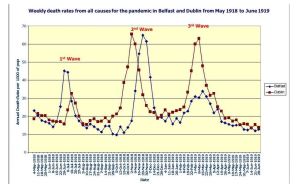

Patricia Marsh’s graph comparing deaths in Belfast and Dublin during the three waves of flu in 1918-19. Available from BBC News.

With COVID-19, we have heard about and may be experiencing a second wave of the infection as during the summer, many countries relaxed strict lockdowns and attempted to return to more normal business. The flu pandemic struck in three waves: the largely unheralded first wave in the summer of 1918, the second wave – the most virulent of the three – in the autumn of 1918 and the almost-as-deadly third wave in the spring of 1919. But not all parts of the country were equally affected. The first cases of the disease were reported in Belfast, and the city and contiguous areas of the north had a relative severe outbreak in summer 1918. While other parts of the country were hit harder by one wave more than others, Dublin, which will receive particular attention here, was hit by all three waves, and particular hard by the second and third (Biener, Marsh and Milne 58-9).

A focus on the second wave of influenza in Dublin in October and November 1918 doesn’t give the whole picture but it does give a good indication of what was happening with cinema in this pandemic. The first wave hadn’t had time to really register in relation to cinema – the resurgence of outdoor pursuits typically made summer cinema’s slow season, in any case – and the third wave’s impact in spring 1919 was very similar, albeit with regional variations, to what happened in the autumn of 1918.

Photographic portrait of Sir Charles Cameron c. 1892 by Sir Thomas Alfred Jones. Source: Wikipedia.

A key figure in the response to influenza in Dublin was a man whom we’ve made the acquaintance of in this blog before, Sir Charles Cameron, Dublin’s Superintendent Medical Officer of Health. Cameron was the most significant figure leading the campaign against influenza including what happened in relation to cinema. Irish born but of proud Scottish parentage, he turned 88 in the summer of 1918 and had been at the forefront of public health in the city for over fifty years. This is not to suggest any kind of incapacity: his advice was clear, practical and measured, and because of his long history of competence, he was a public figure whose pronouncements were sought out by the press and published in the national dailies, which made him the national figure most often quoted on influenza.

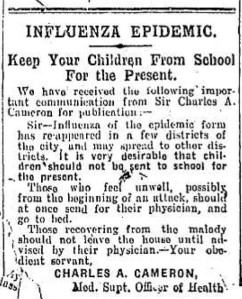

Charles Cameron advises Dublin parents to keep their children out of school; Evening Herald 10 Oct. 1918: 1.

A few influenza deaths in the city at the end of September gave inklings of the second wave, despite the fact that the general health situation looked good (“Weather Bad, Health Good”). By 10 October, however, Cameron was writing to the newspaper telling parents to keep their children out of school (“Influenza Epidemic; Keep Your Children from School for the Present”). He and others believed that the epidemic would reach its peak and begin to decline towards the end of the month.

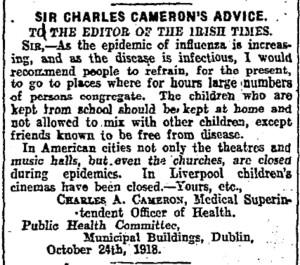

And on 24 October, he again wrote to the papers, and his advice again mostly focused on children, pointing out that they should not only be kept out of school but also have their play monitored, including perhaps avoiding cinema. He advised that “places where for hours large numbers of people congregate” should be avoided and possibly closed, as were theatres, music halls and even churches in America and as were children’s cinemas in Liverpool (“Sir Charles Cameron’s Advice”). This was very tentative and not as explicitly stated as it might have been in the letter, but he expanded it when interviewed by saying that “In America during a somewhat similar epidemic, he understood that churches, cinemas and theatres had been closed for one week, or until the more acute stage had shown signs of passing away, and if the disease continued in Dublin in its present active form it would be desirable to follow the example set by the American authorities in this matter” (“Influenza Epidemic: Outbreak Still Serious”).

A meeting then took place between Cameron and a delegation of the cinema and theatre owners, the full details of which weren’t published but some details emerged in a report in the Belfast News-Letter in which Cameron remarked that “a deputation representing over 50 cinema theatres had assured him, none of the employees of those houses had been attacked by the malady. A promise had, however, been given him that no children would be admitted to such places of entertainment” (“Success of Preventative Measures”).

This ad claimed that Mazda lightbulbs helped purchasers comply with the Lighting Order; Dublin Evening Mail 18 Nov. 1918: 2.

The resistance of the proprietors to further limits on their ability to do business was to some extent understandable given that they faced trade disputes and existing wartime restriction. The newest official restriction was the Lighting Order, which came into effect on 21 October and lasted until the end of February 1919. It stipulated that shops, theatres and banks close during the period in which they would normally be operating and using artificial lighting in order to save coal for the war effort. A correspondent to the Irish Times complained that the Lighting Order was not properly understood, as was shown by the fact that at 6 o’clock “a chemist refused to sell me an aspirin, which I desired to use in a case of influenza” (“Chemists and the Lighting Order”).

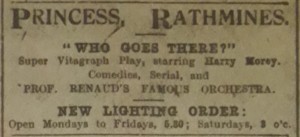

Dublin’s Princess cinema advises patrons of its new opening hours under the Lighting Order; Dublin Evening Mail 28 Oct. 1918: 2.

Some picture houses, such as Dublin’s Princess in Rathmines mentioned the restrictions in its advertising that week. The main part of the order relating to cinemas required that “theatres, picture houses, and other places of entertainment conducted for profit and open to the public during the day, shall be closed on not less than five days in each week between the hours of 3.30 and 5.30 o’clock p.m.” (“New Irish Shop Order”).

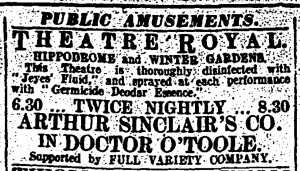

With this curtailment of their opening hours, Dublin cinemas might make concessions, but they weren’t going to close altogether, and Cameron didn’t have the powers to force them to. This occurred in the context of a rising toll that saw 231 deaths in the city for the week ending 25 October (Milne 33). Rather than closure, the theatres and cinemas introduced a hygiene regime using disinfectant and deodorizers. On Thursday, 31 October, the Irish Times reported on a “germicidal campaign” by entertainment venues, using the language of war:

Alive to the imperative need for these safeguards, proprietors and superintendents of places of public amusements are using the most powerful agents of sanitary science to wage war on the deadly micro-organism which has given the influenza its present reign of terror. In the Theatre Royal, Gaiety, Queen’s and Abbey, in the Empire and Tivoli and various cinema houses, throughout the city special attention is given daily to having the buildings most thoroughly ventilated; while the most approved disinfecting preparations are used freely night and day.

The same article gave a few more details of the outcome of Cameron’s negotiations with the theatre and cinema owners: the children they agreed to keep out were those under 14, and they would close their premises for ventilation between 6 and 6.30.

By Saturday, 2 November, the Weekly Irish Times was reporting that there had been a substantial fall in audiences at cinemas, “some of which had a drop of £150 in their booking receipts for the last week” (“Influenza Epidemic in Ireland”). In the Evening Telegraph “Gossip of the Day” columnist JAP confirmed this while commenting on the Larchet Orchestra’s use of Saint Saëns “Danse Macabre” at the Abbey Theatre to “represent a dance of skeletons. […] The ‘Danse Macabre,’ with variations, is an all-pervading melody at the moment, and according to some health experts it sounds nowhere more loudly and insistently than in theatres, music halls, and cinemas. Perhaps they are right. Personally, however, I have noticed fewer ‘dead-heads’ than usual in these places of late” (“Gossip of the Day”).

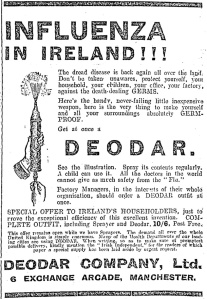

Rather than through music, however, the Weekly Irish Times suggests that the theatres and cinemas sought to reassure and retain or attract back their audiences by attempting to convince them that they were safe because the venues used proprietary cleaning products whose brand names also were assumed to instil confidence. It was safe to go to the Theatre Royal – a legitimate theatre, not a cinema – not just because of its rigorous cleaning and ventilation routine but also because it used Jeyes Fluid and Deodar essence.

An ad for Jeyes Fluid citing cinemas as one of the places in which it can suitably be sprayed; Belfast New-Letter 14 Nov. 1918: 4.

Whatever that combined smell was like, it was no doubt easy for patrons to detect and assumed by the management to provide the necessary reek of reassurance. And in its own advertising that week, the Royal had added these details of cleaning, including the brand names. Ads for Jeyes Fluid and other disinfectants and deodorant sprays would appear in the daily newspapers where they had never been before, citing cinemas among the places where it could be sprayed.

Dublin’s Picture house, Grafton Street claimed to have superior ventilation; Dublin Evening Mail 31 Oct 1918: 2.

Although not all theatres and cinema used a strategy similar to the Royal, several of the ones that tried to appeal to an upmarket audience did, such as the Picture House, Grafton Street, on the city’s most exclusive street. It claimed that it had the right atmosphere because its air “is kept perfectly pure…is washed, warmed and filtered [and] completely changed every few minutes.”

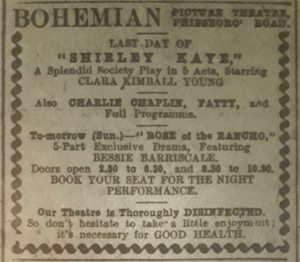

Without going so far into details of processes or products, the north-city Bohemian Picture Theatre claimed to be thoroughly disinfected and that its programme was a tonic. And these cinemas elaborated on these advertising strategies over the weeks, with the Bohemian urging patrons not to hesitate to take a little enjoyment; it’s necessary for good health. Several other cinemas added lines about disinfection to their ads.

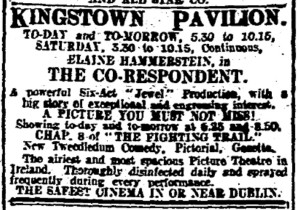

The suburban Kingstown Pavilion indicated it sprayed during the performances; Irish Times 31 Oct. 1918: 2.

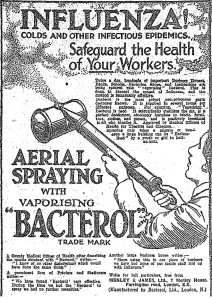

The suburban Kingstown Pavilion went a step further. It claimed to be the safest cinema in or near Dublin not just because it was disinfected daily but also because it was sprayed frequently during every performance. It’s worth emphasizing that the spraying was occurring during performances as audience sat in the auditorium. Although the ads for these aerosols didn’t appear in the daily newspapers until spring 1919, products such as Deodar were clearly already in commercial use. Judith Thissen has written about deodorizing spray used in early cinema, but here they have emerged out of the trade journals to enter the mainstream in the name of the continuation of public entertainment during a public-health crisis.

An ad for Bacterol published in the Irish Times in February 1919 is particularly informative. “Bacterol is the most potent non-poisonous germ destroyer known,” it begins reassuringly. “It scientifically sterilizes the air, is a perfect deodorizer, absolutely harmless to fabric, furniture, clothes, and person, and is positively beneficial to all who breathe it. […] Spraying only takes a minute or two – even a large building can be “Bacterolised” by a youth or girl in half-an-hour.” The ease of use is part of the primary appeal to an employer who wants to “safeguard the health of your workers,” but it also claimed to be “approved by Medical Officers of Health for theatres and cinemas.”

Whether or not audiences believed the claims about the harmlessness and even benefits of inhaling such products is unclear. These were, nonetheless, the ways that Dublin cinemas sought to avoid having to close during the second and the third wave of influenza in 1918 and 1919. The Dublin experience was not the full Irish experience. That was more complex, with local negotiation resulting in cinemas closing in some places and staying open in others. As such, this is only a beginning in the discovery of what Irish cinemas were doing during the 1918-19 flu pandemic.

References

Biener, Guy, Patricia Marsh and Ida Milne. “Greatest Killer of the Twentieth Century.” History Ireland: Ireland After the Rising (2017): 57-61.

“Chemists and the Lighting Order.” Irish Times 25 Oct. 1918: 4.

“Epidemic Is Invited by Panic.” Evening Telegraph 30 Oct. 1918: 2.

“Gossip of the Day: ‘Danse Macabre.’” Evening Telegraph 30 Oct. 1918: 7.

“Influenza Epidemic in Ireland: Heavy Death Toll; Efforts to Combat the Disease.” Weekly Irish Times 2 Nov. 1918: 1.

“Influenza Epidemic: Keep Your Children from School for the Present.” Evening Herald 10 Oct. 1918: 1.

“Influenza Epidemic: Outbreak Still Serious.” Irish Times 25 Oct. 1918: 4.

“Lighting Restrictions.” Irish Times 23 Oct. 1918: 2.

Milne, Ida. Stacking the Coffins: Influenza, War and Revolution in Ireland, 1918-19. Manchester UP, 2018.

“New Irish Shops Order: Restrictions of Hours of Business: Retail and Wholesale Shops, Theatres, and Banks Included.” Irish Times 23 Oct. 1918: 3.

“Sir Charles Cameron’s Advice.” Irish Times 25 Oct. 1920: 4.

“Success of Preventative Measures.” Belfast News-Letter 2 Nov. 1918: 8.

Thissen, Judith. “Perfuming Devices, Purifying Discourses: The American Trade Press’ Fight against Filthy Theaters and Foul Air.” Early Popular Visual Culture 16:4, 342-354. DOI: 10.1080/17460654.2018.1553055.

“Weather Bad, Health Good.” Evening Herald 24 Sep 1918: 1.

Pingback: Ominous Flickers and Fade Out for Irish Cinema in 1920 | Early Irish Cinema