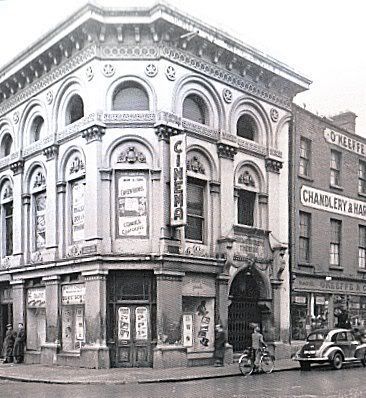

Mary Street Picture House sometime in the 1950s. Image from Pintrest.

On the 3 August 1918, five boys aged between 11 and 14 were convicted before Dublin’s City Commission court of having stolen a film from the Mary Street Picture House, one of the cinemas owned by Alderman John J. Farrell and managed at the time by William Bowes. Charles and Thomas Boland, Laurence Fitzgerald, James Gaffney and John Dillon (for brevity, the Boland gang) broke into the cinema on 3 July and took the 2,000-foot film to a vacant room in nearby Jervis Street.

Extract from the 1911 census return of the family of Charles and Thomas Boland, who were 4 and 6 years old at the time and living with their parents in a tenement room at 23 Greek Street, Dublin.

While their three co-defendants pleaded guilty, the Boland brothers denied the charge, claiming that they had merely found the film in a cellar, and Charles had then brought a portion of it to Bowes, which is how their role in the incident was discovered. However, all the boys were found guilty, with Justice Pim freeing them on the undertaking that their families would ensure their good behaviour for two years (“Dublin Boys Steal a Cinema Film”).

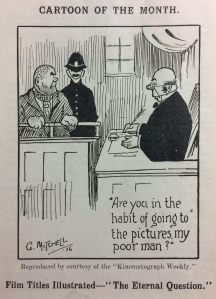

The incident was a minor one, and only received more than passing mention from the Dublin Evening Mail because of a detail the editor no doubt thought would amuse his/her readers. Offering some insight into the boys’ motives for the theft, arresting officer Constable Holmes claimed to laughter from the court that they had intended to transform their vacant room into a picture house of their own.

Extract from the 1911 census return for the family of John Dillon (4 at this time), the only other one of the convicted boys who can be readily identified in these records. The nine members of his family were living in two tenement rooms at 16 Green Street, across the road from the courthouse in which the boys were tried.

In the context in which picture houses were owned by such prominent businessmen as Farrell, it did seem incongruous that a group of pre-teens from the tenement slums might establish a cinema in an abandoned house. However, inconveniently for such businessmen, the story also suggests that cinema had not yet escaped its public association with criminality, and particularly the criminal behaviour of working-class boys. The most highly publicized case of this in Ireland had been the crime spree by Clutching Hand gangs in 1916.

And beyond picture-house proprietors, this continued presentation of cinema as a juvenile-delinquent medium in 1918 would doubtless have caused chagrin to such promoters of the industry as the cinema magazine Irish Limelight. Ridiculing these tropes in an editorial a year-and-a-half previously, it had observed that “[t]he ‘Saw it on the Pictures’ plea has now lost its force as an argument against the Cinema as a favourite excuse of parents who have neglected to control their erring boys” (“Lesson from History”).

The awful state of housing for Dublin’s working-class families was revealed by a Dublin Corporation report in 1914, which included this image of dilapidated houses in Jervis Street. The report is available here.

It’s not clear if the Limelight commented on this incident because its issues for August and September 1918 are not extant, but it is worth pausing on it to distinguish between the different ways boys may have been said to have erred in their interactions with cinema at this period. The “Saw it on the Pictures” plea was just one of those interactions, but it does seem to be operating in the case of the Clutching Hand gangs, where the screen actions of a master criminal provided an imaginative resource to be emulated. While the Limelight and others were right to point out that blaming the cinema for criminal behaviour had become a cliché, often sensationalized to a moral panic, they were not right to imply that no behaviour treated as criminal was inspired by film viewing Watching films did at least occasionally have a demonstrable effect on audience members.

A 1913 photograph of a tenement room in Dublin’s Francis Street with poor furnishings but some images on the walls; from the Royal Society of Antiquaries in Ireland’s Darkest Dublin (RSAI DD) collection, available here.

In relation to the indictable behaviour of the Boland gang, however, what was on the screen seems less important than the presence of the Mary Street Picture House close to where they lived. The advent of cinema brought picture houses into local communities where venues providing professional entertainment had never existed before and at a relatively low cost. In this regard, the case resembles the conviction of four other Dublin boys for property damage following their night at the Brunswick Street Picture House in October 1916, after which they camped out in an uninhabited and condemned house they were later convicted of damaging.

A single tenement room in the Coombe area of Dublin in 1913; RSAI DD, No. 83.

But the Boland gang differed from these 1916 boys in having committed their crime in the picture house itself. Not that stealing from picture houses was unprecedented. Indeed, Thomas Murphy of 7 Jervis Street had stolen the safe from the Mary Street Picture House in April 1915, a case notable because he was convicted on fingerprint evidence (“City Cinema”). They weren’t even the first Irish boys to steal a film. On 9 October 1917, a boy named David Kennedy of Downing Street, Belfast, was successfully prosecuted in the city’s Custody Court for having stolen a film from the Great Northern Railway Company. The staff at the company’s parcel office had given him the film because they recognized him as having collected films for the Princess Picture Palace in the past. His father told the court that his son had “pictures on the brain” and wanted to go to the pictures all the time. It’s not clear if this compulsion to go to the cinema was the motive for the theft and subsequent sale of the film in Smithfield market for 2s 6d. If it was, Kennedy had undervalued his loot. ”The film was a ‘Chaplin’ one,” the Northern Whig noted, “and worth about £20” (“Belfast Police”).

Nevertheless, regardless of how little of their plan they realized, the Boland gang members contrast with Kennedy in their deeper engagement with cinema. They did not have just pictures on the brain; they had the wider institution of cinema on the brain. They had stolen the film as part of the procurement process that would allow them to set up their own alternative picture house. Given that the Mary Street management valued the film at £90 – an amount, incidentally, at odds with £20 mentioned in the Belfast case – robbery was really their only option to get control of cinema.

One of a series of ads promoting recruitment to the air force and navy; Dublin Evening Mail 29 Aug. 1918: 4.

As well as these poor boys, promoters of military recruiting in Ireland also had cinema in their sights, if not on the brain, at the end of August 1918. Earlier in the year, the British government’s attempted introduction of conscription of Irishmen into the British army had been defeated, or at least postponed, by the unprecedented alliance of all elements of nationalist Ireland, but this had not stopped regular voluntary recruitment. Appealing to a widespread interest in such new technologies of war as the submarine, the airship and the tank, an extensive summer press and poster campaign attempted to suggest that the air force or navy might be more acceptable alternative forms of military service to the army for Irishmen.

Ad for the first of the mass recruitment meetings on Dublin streets by Arthur Lynch and James O’Grady; Dublin Evening Mail 24 Aug. 1918: 4.

Two Westminster MPs of Irish descent came to Dublin to make a personal, oratorical appeal to “patriotic young Irishmen” to join up but were forced to use the cinema as an alternative way of reaching their audience. Australian-born Colonel Arthur Lynch, who had led an Irish brigade against the British during the Boer War and was MP for West Clare, and Captain James O’Grady, an English-born Labour MP, first addressed a meeting outside the Recruiting Office headquarters in Kildare Street on 24 August. Following its success, they organized a series of mass recruitment meetings on the city streets: at the Fountain in James Street on 27 August, on Amiens Street on 28 August and at Smithfield on 29 August. Others around the country were to come.

A cartoon postcard circulating in Dublin in July 1918 expressing the counterproductiveness of forcing conscription on Ireland. Joseph Holloway’s reproduced a copy in his diary on 6 July; this copy is available here.

However, Sinn Féin protestors successfully disrupted the James Street meeting by drowning Lynch out “in a hurricane of groans, shrieks, ‘voices,’ and discordant cat-calls” (“Recruiting Campaign”). Indeed, when Lynch and O’Grady had left the scene, Sinn Féin speakers made speeches from the lorry that had been brought as their platform. “Soon recruiting meetings will be proclaimed,” Joseph Holloway commented wryly in his diary, “as they are providing splendid Sinn Fein demonstrations.” When the Amiens Street meeting delivered a similar occasion, the Smithfield meeting was abandoned, and Lynch complained he had been denied free speech and sought in vain a public debate on recruiting with Sinn Féin representatives.

The text Lynch intended to project on Dublin cinema screens to attract recruits to his Irish Brigade; Dublin Evening Mail 30 Aug. 1918: 3.

But he also made plans to use the picture houses, which everybody seemed to agree had a particular attraction for boys and young men. On 30 August, the Dublin Evening Mail included the text of a “message to Young Ireland” to join Lynch’s Irish Brigade that he intended to “be flashed on the screen at cinemas in Dublin and afterwards throughout Ireland” (“Colonel Lynch on the Screen”). But Lynch’s cinematic adventure went beyond a text-based ad. “A film has also been taken of Colonel Lynch and Captain O’Grady,” the Mail report concluded, “and this will also be displayed on the screen in Dublin next week, and afterwards throughout the various picture halls in the country.”

No surviving evidence appears to exist to confirm that the ad and/or the film were shown in Dublin the following week. Although propaganda films were not uncommon, the controversy Lynch and O’Grady caused in the streets might have been enough for nervous cinema managers to keep them off the screen. In any event, the summer of 1918 saw Irish politicians and military recruiters join boys from the tenements in trying to hijack the cinema for their own purposes.

References

“Belfast Police – Yesterday.” Northern Whig 10 Oct. 1917: 3.

“City Cinema Broken into and Robbed: Evidence of Finger Prints.” Evening Telegraph 29 Apr. 1915: 3.

“Colonel Lynch on the Screen: His Message to Young Ireland.” Dublin Evening Mail 30 Aug. 1918: 3.

“Dublin Boys Steal a Cinema Film: To Start Their Own Picture House.” Dublin Evening Mail 3 Aug. 1918: 3.

Holloway, Joseph. Holloway Diaries. National Library of Ireland.

“A Lesson from History.” Editorial. Irish Limelight Feb. 1917: 1.

“Lure of the Films: City Boys Who Wanted a Cinema of Their Own.” Evening Telegraph 3 Aug. 1918: 1.

“Recruiting Campaign: Colonel Lynch Denied a Hearing.” Evening Telegraph 28 Aug. 1918: 3.