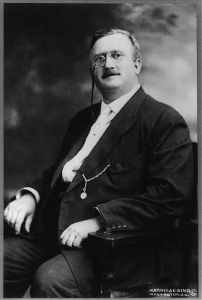

Irish-American James Mark Sullivan, who co-founded the Film Company of Ireland in March 1916. Image from the Library of Congress.

Although Ireland is celebrating the centenary of the 1916 Rising in March 2016, Easter was celebrated in 1916 in late April. Nevertheless, March 1916 saw such momentous cinematic events as the founding of the first major indigenous film production company. And even if Easter itself was still some way off, Irish cinema hit the beginning of the Easter season. In what was clearly a coordinated move by the Irish Catholic hierarchy, several bishops mentioned cinema in their Lenten pastorals, the letters from them read out on 5 March 1916 in churches in their dioceses to mark the start of the 40-day fasting period leading up to Easter. “Immodest representations in Theatres should be reprobated by every good man, and every effort should be made to discountenance them,” ordered the Bishop of Cork, but he had a particular warning about cinema:

We desire to direct your attention particularly to cinematograph and picture shows. The films come from outside, and from places where what concerns Christian modesty is made little of, and there is always a danger that what is unfit to be seen may be exhibited unless constant watchfulness is exercised to exclude what is objectionable and offensive in a Catholic country.(“Lenten Pastorals.”)

This call for “constant watchfulness” was an intensification of the hierarchy’s involvement in the church’s efforts to control cinema. If the church could not prevent people going to picture houses altogether, it was determined that it would shape what, where and when people would watch. The initially mainly lay Vigilance Committees had in late 1915 been put under centralized clerical control as the Irish Vigilance Association, which held a mass meeting at Dublin’s Mansion House that sent a renewed demand for the introduction of a specifically Irish film censorship (“Mansion House Meeting”). The many local campaigns against the opening of picture houses on Sunday were also led from the altar. “At different Masses on Sunday last in the four parish churches, as well as in the Black Abbey and Capuchin Friary,” reported the Kilkenny People, “a strong appeal was made to the people to abstain from attending the local Picture House on Sundays, particularly during Lent” (“Sunday Cinemas in Kilkenny”).

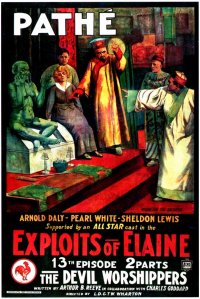

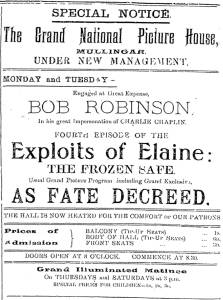

Ad for Stafford’s Longford Cinema in St Patrick’s week included an episode of The Exploits of Elaine (US: Wharton, 1914), the serial that featured the master criminal the Clutching Hand. Longford Leader 11 Mar. 1916: 3.

In making their calls for vigilance, the bishops could indicate the harmfulness of cinema by citing the ongoing trial of a gang of boys in Mullingar who had committed robberies inspired by onscreen criminals. The papers reported many similar cases including the prosecution of 20-year-old ex-sailor James J. Sloan who told the Belfast Assizes that his house-breaking equipment was “the materials Charlie Chaplin works with” (“Items of Interest”). The prominence of such stories led James Stafford of the Longford Cinema to refute publicly the claim made by a boy charged with larceny at the local petty session that he had committed the robbery to get money to go to the pictures. “I have made it a point not to admit to the Longford Cinema Theatre boys of this class,” Stafford contended, “and this boy in particular is one of several of his class whom I frequently refused admission” (“Unfounded Allegation”). As the Mullingar case suggests, the class he referred to was the poorest of the working-class.

The cinema industry long feared the imposition of crippling taxes, going so far in this cartoon as to identify the British government with the zeppelin raids then terrorizing southeast England. Bioscope 7 Oct. 1915: 16c.

The British government also had a vigilant eye on the cinema industry in Britain and Ireland as a way of raising needed war funds. Months before the imposition of an amusement tax in the May 1916 budget, there was much discussion of its likely effects on the industry and how it was to be collected. “The view which at present commends itself to the authorities,” reported the Irish Independent, “is that the Government should print the tickets for the cinema shows, and these should be purchased from the Government by the trade at a price which would cover the tax” (“Proposed Cinema Tax”). As well as further binding the cinema industry to the British war effort, the tax would alter the working-class nature of cinema. “Upon the injustices of a penny per seat tax there can be not two opinions,” argued Frank W. Ogden Smith in the trade journal Bioscope,

and if such a tax be allowed to pass unchallenged this point must be borne in mind – when we revert to peace times it will mean the cinema as a poor man’s amusement and recreation will have ceased to exist, for the Government having tasted the fruit and found it refreshing in actuality not theory, will not be likely to relinquish the tax. (“Passing of the Penny Cinema.”)

Longford and Mullingar were just two of the Irish places where this process could be most clearly seen in March 1916.

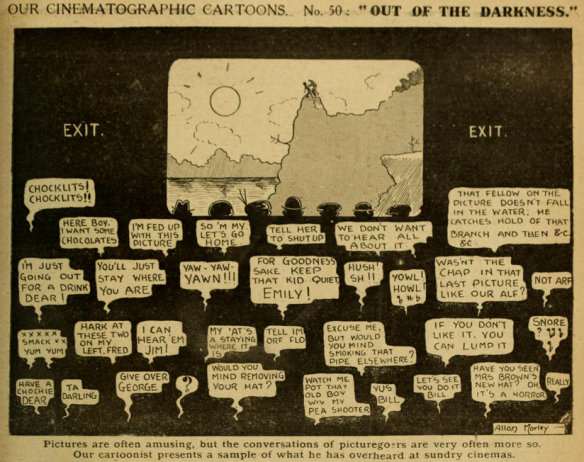

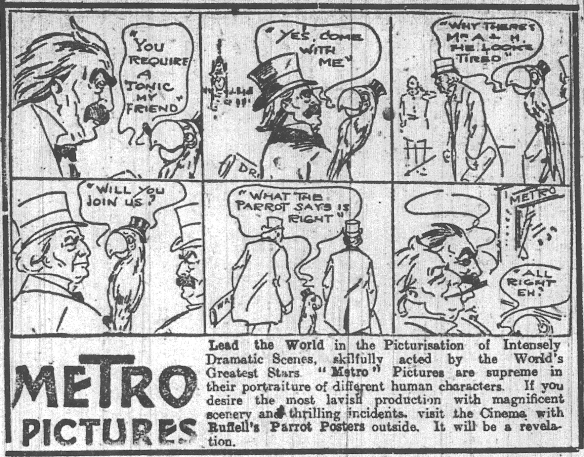

The industry as a whole – including the Bioscope – had long courted an audience far beyond the penny cinemagoer, and it did so in a climate in which many doubted that cinema represented a quality contribution to culture. At a meeting of the Cork County Council, the chairman complained that the large amount of money spent on technical education was wasted because “the people for whom it was intended showed no disposition to profit by it.” Instead, the popularity of Charlie Chaplin and picture houses were proof, he believed, of the failure of the art classes provided to raise the public taste (“Cork County Council”). Publicity strategies to counter such views and promote films and picture houses as quality entertainment were important, and one ad campaign stood out in Ireland in March 1916. Metro’s British agent Ruffells’ Exclusives was pioneering in marketing film brands to the Irish public. Ads for Metro had been appearing in newspapers for some time when the Bioscope reported that Ruffells in Dublin abandoned their trademark parrot for another animal in order to stage a spectacular publicity stunt: “This consisted of six donkey carts, all passing the leading station and advertising on large boards the display of Metro pictures. The houses showing the films were the Bohemian, the Carlton, the Grafton Street and Grand” (“Trade Topics”).

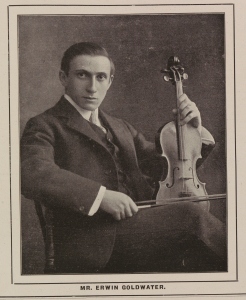

These named picture houses were among Dublin’s most prominent cinemas, and each watched what the others were doing. What they were doing to ensure success was to provide lavishly comfortable buildings, feature such highly publicized films as Metro’s and offer novel musical accompaniment. Located in Phibsboro outside the city centre, the Bohemian had attracted patrons since its opening in 1914 by advertising the best musical attractions in the city. The Bohemian’s orchestra consisted of 16 musicians under musical director Percy Carver. With the increasing competition for cinema patrons in the city centre, the Carlton as the latest-opened picture house sought to secure its audience by adding to its musical attractions. Beginning on Patrick’s Day, 17 March, the Carlton challenged the Bohemian’s musical pre-eminence by engaging the concert violinist Erwin Goldwater. The Irish Times called this “[a] new departure in connection with cinema entertainments [that] takes the form of a violin recital by Mr. E. Goldwater, a pupil of Sevcik, and formerly first violin at the Royal Opera, Covent Garden. Mr. Goldwater will conduct the orchestra at the Carlton” (“Platform and Stage”).

Goldwater’s engagement was not the only significant event that picture-house proprietors planned for the holiday of the Irish patron saint. A company led by I. I. Bradlaw, David Frame and Henry Grandy reopened the Clontarf Cinema in the former Clontarf Town Hall. “It has been re-decorated and reconstructed throughout in the most luxurious manner,” the Evening Telegraph announced, “and will be found to be equal in every respect to the very best picture houses in the city” (“The Cinema, Clontarf”). Several picture houses offered special programmes of Irish films and/or music. Perhaps the most surprising of these was at Belfast’s CPA (Central Presbyterian Association) Assembly Hall. “Five reels of well-selected cinema were screened, and the premier place amongst these was taken by “Brennan of the Moor,” a three-part filmisation of the Irish story,” revealed the Northern Whig. “Mr. F. J. Moffett presided at the organ, and also acted as accompanist. Mr. W. R. Gordon sang several Irish folk-songs in a most pleasing manner” (“C.P.A. Entertainments”).

Although Brennan of the Moor (US: Solax, 1913) was revived on occasion, the most popular films to constitute an Irish programme were still those made by Sidney Olcott and Gene Gauntier for Kalem and other companies in Ireland between 1910 and 1914. Nenagh’s Ormond Kinema Company provided films – including an unnamed Chaplin and The Colleen Bawn (US: Kalem, 1911) – free of charge to the Toomevara and Nenagh Hurling Club after their fund-raising concert in Nenagh’s Town Hall on 17 March (“St. Patrick’s Night’s Concert”). “Some unique films of the famous Tubberadora, Toomevara, and Thurles Teams” were also shown (“The Coming St Patrick’s Night Concert”). The Colleen Bawn was the most popular of Dublin-born Dion Boucicault’s stage melodramas, but productions of his more political Arrah-na-Pogue and The Shaughraun were particularly evident in March 1916. In early March 1916, The Shaughraun (US: Kalem, 1912) – which featured an escaped Fenian – was revived at both Dublin’s Rotunda and Bohemian; during the same period, a stage version was produced at Dublin’s Father Mathew Hall by the Barry Sullivan Society, while at the Hibernian Hall, Parnell Square, the Hibernian Players staged Arrah-na-Pogue. The Olcott and Gauntier’s Arrah-na-Pogue (US: Kalem, 1911) was shown at the newly refurbished Omagh Picture House on St Patrick’s night (“Omagh Picture House”). The Rotunda’s programme for St Patrick’s day and the two days following included two other of Kalem’s Irish-shot films: the 1798 drama Rory O’More (US: Kalem, 1911) and The Fishermaid of Ballydavid (US: Kalem, 1911).

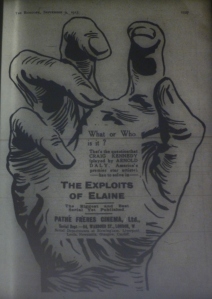

Small ad from the Film Company of Ireland seeking Irish scenarios; Freeman’s Jorunal 9 Mar. 1916: 2.

The Kalem films were so regularly revived in part because no fiction films had been shot in Ireland since Olcott had stopped coming to Ireland following the outbreak of the war. In March 1916, this situation was about to change with the founding of the most important indigenous Irish film production company of the silent period. On 2 March, Irish American lawyer and diplomat James Mark Sullivan and Henry Fitzgibbon registered the Film Company of Ireland (FCOI) at Dublin’s Companies Registration Office. The FCOI had little early press coverage. “The objects are to establish, organise and work in Ireland the manufacture and construction of cinema films of every description,” reported the Freeman’s Journal, seemingly reproducing the information on the company registration form,

and to engage in the making of scenic and dramatic moving pictures, and in the sale and exchange of cinema pictures, and to engage in the employment of skilled and unskilled labour, and of all such artistes, authors, and performers as the development of the business may require. (“An Irish Film Company.”)

Ads that appeared in the papers on 9 March specifically sought authors of “photo play scenarios, preferably with Irish atmosphere and background.” These ads gave the address of the FCOI’s offices as 16 Henry Street, uncomfortably close to the GPO, soon to be the major site of the Easter Rising.

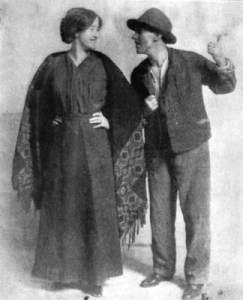

J. M. Kerrigan with Sara Allgood in a 1911 Abbey touring production of The Playboy of the Western World. Image from Wikipedia.

The FCOI also sought actors, and here Joseph Holloway’s diary offers an intriguing early insight. When actor Felix Hughes answered an FCOI ad for actors, he “was astonished on entering the manager’s room to see Joe Kerrigan quite at home there with his back to the fire – the manager was seated at a table & spoke with the twang of a Yankee.” Kerrigan was one of the Abbey Theatre’s leading actors, and Hughes was surprised to encounter him seemingly embedded with Sullivan in the FCOI. However,

Kerrigan spoke up for him & said to the manager, “he’s the very one we want,” (evidently K is to be the star actor in new Co. & has some monetary interest in it as well.) “He has played at the Abbey & travelled with Co to London.” So the manager said, “We must have Felix,” & entered his name & address & said, “he would hear from him in the course of four or five weeks time when all arrangements were fixed up to begin operations. (Holloway, 21 Mar. 1916).

As its operations began, the FCOI gave the hope that cinema would not just be something that the authorities constantly surveilled but would produce challenging films for burgeoning Irish audiences at a historical moment.

References

“The Cinema, Clontarf.” Evening Telegraph 16 Mar. 1916: 2.

“The Coming St Patrick’s Night Concert.” Nenagh News 11 Mar. 1916: 4.

“Cork County Council: Annual Estimate.” Cork Examiner 1 Mar. 1916: 3.

“C.P.A. Entertainments.” Northern Whig 20 Mar. 1916: 7.

Holloway, Joseph. Holloway Diaries. National Library of Ireland.

“Items of Interest: A Youthful Burglar” Irish Independent 17 Mar. 1916: 4.

“An Irish Film Company.” Freeman’s Journal 4 Mar 1916: 2.

“Lenten Pastorals: Diocese of Cork.” Cork Examiner 6 Mar. 1916: 7.

“Mansion House Meeting: Message from the Pope.” Freeman’s Journal 14 March 1916: 3.

Ogden Smith, Frank W. “The Passing of the Penny Cinema.” Bioscope 9 Mar. 1916: 1008.

“Omagh Picture House: Extensive Alterations.” Ulster Herald 18 March 1916: 5.

“Platform and Stage.” Irish Times 18 Mar. 1916: 7.

“Proposed Cinema Tax.” Irish Independent 23 Mar. 1916: 4.

“St. Patrick’s Night’s Concert.” Nenagh News 18 Mar. 1916: 3.

“Sunday Cinemas in Kilkenny.” Kilkenny People 18 Mar. 1916: 5.

“Trade Topics.” Bioscope 30 Mar. 1916: 1377.

“An Unfounded Allegation Contradicted.” Longford Leader 25 Mar. 1916: 2.