“It is ever so much more a patriotic thing to go down the quays and give the soldiers a good send-off than it is to sit in a darkened picture house watching, perhaps, ‘shadow soldiers’ flickering on a screen,” reported Paddy, the Ireland correspondent of the British cinema trade journal Bioscope in August 1914 explaining the falloff in attendance at Dublin’s picture houses at the start of the Great War. “[T]he fact that the Lord Mayor of Dublin had to publicly ask the people through the medium of the Press, to refrain from causing a block on the quays and assist in getting the soldiers embarked more expeditiously shows how matters stand” (Paddy, 13 Aug., 673). Mobilization affected the cinema and its relationship with the popular audience in various ways. Those who lined the Dublin quays, Paddy suggested, were particularly the popular audience who would otherwise have occupied the picture houses’ cheapest – usually three-penny or 3d. – seats. Although Frederick Sparling, manager of Phibsboro’s Bohemian Picture Theatre, reported brisk business, “he experienced a great falling off in the attendances at the 3d. seats, and he expected that receipts generally would show a drop for a little time” (ibid).

Paddy claimed that the effect in Ulster was quite different, with the outbreak of the war bringing unionist and nationalist audiences together in the face of a common enemy. “[T]he one-time rivals now fraternise,” he observed, “and quiet, law-abiding and gaiety-loving citizens are now taking their pleasures with less sadness than had been their wont during the two gloomy years from which Ireland has just emerged” (Paddy, 13 Aug., 675). Unfortunately, this somewhat unlikely harmony would be short-lived because the difficulties of procuring enough flax and other raw material for Ulster’s factories would mean that mill workers, “the backbone of the support of the cinema in Ulster as in other manufacturing centres,” would be placed on half-time working at half-pay, leaving “nothing to spend on amusements of any description” (ibid).

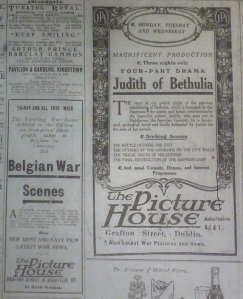

Actuality films of the war appeared on the cinema programme alongside such fiction film as D. W. Griffith’s Judith of Bethulia (US: Biograph, 1914). Dublin Evening Mail 24 Aug. 1914: 2.

Nevertheless, Irish picture houses attempted from a very early point in the war to provide shadow soldiers on the screen for their audiences, and not only working-class ones. On 7 August 1914, the Dublin Evening Mail carried the first of a series of unusually large ads for the Picture House, Grafton Street and the Picture House, Sackville Street showing films depicting “the latest developments of the War, day by day.” Both of these cinemas were owned by the London-based chain Provincial Cinematograph Theatres, which also ran the less-salubrious Volta in Mary Street and Belfast’s Picture House, Royal Avenue. The company promoted its venues – and particularly the recently renovated and extended Grafton on Dublin’s most prestigious shopping street – as offering luxuries suitable for prosperous city-centre shoppers. Strollers who stopped into the Grafton’s public café might be induced to see the war pictures by a sign that indicated which of the six-to-eight films typically on a cinema programme was currently playing in the auditorium.

Although such passersby or Evening Mail readers arrested by the prominent ads continued to be offered a programme of films after the outbreak of hostilities, they seem to have been presented with an overwhelming number of war-themed films. The Grafton featured England’s Menace (Britain: London, 1914), a “stunning naval drama,” for the week beginning 10 August, the six-day run representing twice the usual period for which a film was shown. For the first three days of the following week, the Grafton exhibited Maurice Elvey’s In the Days of Trafalgar (Britain: British and Colonial, 1914), supported by a programme that included the first part of the British Army Film (Britain: Keith Prowse, 1914), the second part of which ran in the latter half of the week on a bill headed by The Spy, or The Mystery of Capt. Dawson (1914), a detective drama involving the stealing of plans for a new quick-firing gun. The Belgian War Scenes advertised on 24 August were said to have come “from actual photographs [i.e., films] taken in Belgium on Thursday last,” and these played on the programme with D. W. Griffith’s Judith of Bethulia (US: Biograph, 1914), an adaptation of the biblical Book of Judith’s story of war and decapitation.

Provincial was not the only cinema proprietor to show actual war footage – Dublin’s Rotunda, Phoenix and Bohemian all advertised their latest war films, as did many others in newspapers or through more ephemeral forms such as posters and handbills that no longer survive. Provincial, however, made a special effort to exhibit the actualities in programmes with other kinds of war-themed films to cater for – or indeed, help to create – a patriotic war fever. Given the recentness of the war, none of the fiction films just mentioned concerned the current conflict with Germany, nor did the British Army Film, a documentary about ordinary life in the army that was made before the war and that had attracted a protest in March. There was nothing new in popular culture assembling and re-presenting pre-existing elements in a new combination that served the prevailing ideology, particularly at a time of crisis. The live music that accompanied silent film in picture houses of the 1910s could add further jingoism. There were precedents for the use of film in war-time patriotic shows as early as the Boer War, but the popular audience in many parts of Ireland had often been vocally resistant to such anti-Boer/pro-British jingoistic shows (Condon).

What had changed between the turn of the century and the 1910s, however, was cinema’s place within the mediascape in Ireland as elsewhere. By 1914, Ireland had a large number of picture houses that provided news alongside dramatic entertainment. Although picture houses could not match the newspapers’ detailed coverage of topical events, newsreels from the front provided by such companies as Pathé and Gaumont offered something the press could not: moving images of battle sites and the people who fought in the war. Because newsreel scenes recorded on film needed to be physically transported from the front, their newsworthiness had dissipated. Some picture theatres, including the Grafton and Sackville, entered into agreements with telegraphic wire services to offer instantaneous messages during shows, a phenomenon that bears resemblance to a Twitter feed. One ad for these picture houses informed the public that “[a]rrangements have been completed with the Central News Agency for a complete service of telegrams from the Front, to be supplied to this Theatre. As the news arrives it will be immediately thrown on to the screen” (“The War”).

As the war began, commentators in the press debated cinema’s place among other media. To some, it was an absurd form. “In a city picture house, a man tells me,” confided Dublin’s Evening Herald columnist The Man About Town in mid-August 1914,

he has just acquired some curious and too little known facts about the Roman Empire. It would appear that the Caesars were in the habit of decorating their apartments with busts of Dante (which certainly showed remarkable foresight on their part), while their consorts sought relaxation by perusing printed volumes, handsomely bound. Verily, to live is to learn, but seeing is not always believing.

Seeing the past – or present – in the form of the “cineanachronisms” provided in the picture houses was not to be believed by this canny man about town. At least not always.

Other commentators took a more considered but not uncritical view of what had become the country’s most ubiquitous theatrical entertainment, reaching parts of small-town, rural and suburban Ireland that had never had regular professional theatrical entertainment before. By the end of 1914, Dublin Corporation approved licences for 25 premises to show films, with two or three others also under consideration. A small group of these were the theatres – the Theatre Royal, Tivoli Theatre, Empire Theatre and Queen’s Theatre – that had been showing films for two decades or more as part of their mainly live theatrical entertainments. The rest were dedicated picture houses in which the main entertainment was the projection of recorded moving pictures onto a screen, with the live elements limited to musical accompaniment, vocalists who sang between films, and in some venues, one or more variety acts. “Personally, I think we are carrying the picture business to excess,” opined the Dublin Evening Mail’s “Music and the Drama” columnist H.R.W. “The opening of theatres [i.e., picture houses] in the suburbs has much to commend it, but the many additions to the already large number of picture houses in the city is rather risky enterprise” (“War and the Drama”). This was not just a problem among competing picture house owners, but also among theatres proprietors because “ [t]he increasing popularity of the Picture Theatre is making the future of the drama and the music hall a serious problem” (“The Invasion of the Film”). H.R.W. felt that Dublin theatre managers had allowed this to happen by offering increasing amounts of music-hall entertainment and neglecting drama:

the vast public which desires something romantic and dramatic has been catered for by the activity of picture theatres, which, with their cheapness, the casual nature of the performances, and the liberty of smoking, has earned for them a considerable degree of popularity. (Ibid.)

By the outbreak of the war, cinema had become a truly mass medium, providing both news images and dramatic entertainment in a very particular setting. Even without overt propaganda films, individual picture houses or cinema chains could in their choice of films, music and other elements of their programmes present the war in ways that influenced the popular audience that governments needed to prosecute the war. If the Irish popular audience was indeed crowding the quays waving off Irish soldiers, it seemed likely that they would return to the picture houses to cheer on the screen’s shadow soldiers.

References

“Belgian War Scenes.” Advertisement. Dublin Evening Mail 24 August 1914: 2.

Condon, Denis. “Receiving News from the Seat of War: Dublin Audiences Respond to Boer War Entertainments.” Early Popular Visual Culture 9:2 (May 2011), pp. 93-106.

H. R. W. “Music and the Drama: War and the Drama.” Dublin Evening Mail 3 Aug. 1914: 2.

—. “Music and the Drama: The Invasion of the Film.” Dublin Evening Mail 27 Jul. 1914: 4.

The Man About Town. “Cineanachronisms.” Evening Herald. 13 Aug. 1914: 2.

Paddy. “Pictures in Ireland.” Bioscope 13 Aug. 1914: 673-5.

“The War: Picture House News Service.” Advertisement. Dublin Evening Mail 12 Aug. 1914: 2.