“The pictures are luring the Dublin public,” JHC observed in the Irish Independent‘s “To-Day & Yesterday” column on 12 July 1922. “People are taking ‘a fearful joy’ in re-witnessing the ordeal they passed through… The events of the past fortnight fulfil Lessing’s exacting definition of drama – life with the dull parts left out.” The events JHC was referring to are the Battle of Dublin, the engagement that opened the Irish Civil War. That battle began on 28 June, when National Army troops attacked anti-Treaty IRA forces occupying the Four Courts, using artillery loaned by the British government. The bombardment had the desired effect of forcing the occupiers to surrender on 30 June, but not before the destruction of the Public Records Office. Further IRA units located in the O’Connell Street area continued the battle until 5 July, by which time, they too were surrounded and defeated by the National Army’s superior numbers and fire power. At the end of eight days of fighting, the Four Courts and parts of Upper O’Connell Street were in smouldering ruins, and around 80 people had been killed, approximately 35 of whom were non-combatant city residents (Dorney).

Dubliners had seemed ready to see films of the Civil War by 12 July, but only that week. When the fighting had stopped a week earlier, JHC wasn’t talking about the fearful joy in rewitnessing its events at the cinema. “Times of trial sometimes prompt the craving for amusement,” s/he had argued. “In the beginning of the struggle the picture-houses were well patronised. But yesterday saw them quite forlorn although they offered an up-to-date programme of the ‘battle scenes’ and ‘Four Courts incidents’” (5 Jul.). Which cinemas JHC was referring to is unclear to us now, in part because none of the city-centre cinemas advertised in the early part of that week, and certainly the ones in the O’Connell Street area couldn’t have opened until the shooting stopped and fires were extinguished. Those that had been closed or pressed into other uses were the Sackville at 51 Lower O’Connell Street, the Grand Central at 6-7 Lower O’Connell Street, the Metropole at 35-39 Lower O’Connell Street, La Scala at 4-8 Princes Street, the Pillar at 52 Upper O’Connell Street, the Carlton at 62 Upper O’Connell Street, the Rotunda at 165 Parnell Street and the Corinthian at 4-6 Eden Quay.

“The last couple of very stirring weeks were not wanting in their effect on cinema houses,” the Freeman’s Journal’s “Cinema Notes” columnist observed on 10 July. “The Metropole was made a Red Cross centre, and La Scala was a point for bombardment by the National troops of their opponents on the opposite side of O’Connell street.” Mentioning the other cinemas in the area, the writer commented that “the entire marvel of the whole thing, from the picture house point of view, is that we still have these places, none or very little the worse for wear, in which to spend our evenings.” The Irish Time‘s “Cinema Notes” writer echoed these thoughts five days later, adding that

the Sackville and the [Grand] Central Cinemas came through the ordeal almost unscathed. The Corinthian Cinema on Eden quay seemed to have been selected as an Irregular sniping post, and its parapet bears traces of bullet marks.

The other picture theatres in the city had, of course, to close their doors while the battle raged, but they are preparing to reopen. It is to be hoped that business will come back to them in increasing volume, and thus in some measure make amends for the slump which has been felt in Dublin and elsewhere during the past few months.

This suggests that even ten days after the fighting ended, some cinemas were not yet reopened.

The cinemas had certainly been lucky. “Some special god seemed to have been keeping a friendly eye on them,” this writer thought. But even if they didn’t feature on the lists of destroyed buildings, the cinemas weren’t entirely unscathed. The earliest surviving photograph of the Pillar shows it on the busy streetscape of Upper O’Connell Street just after the fighting stopped, with many pedestrians passing its bullet-damaged canopy, even if its façade seems somehow to have fared better than the buildings around it. “Considering its exposed appearance,” an Evening Herald reporter noted, “the Pillar Picture House escaped fairly well. Only a few bullets penetrated the big glass doors, but in the offices overhead a machine-gun had played for some time and did damage to the interior” (“Awe-Stricken Crowd”). It may be for that internal damage that the Pillar applied for compensation to the city for the figure of £750 (“Dublin’s Bill”).

The Corinthian was the first of the city-centre cinemas to resume advertising – but not necessarily the first exhibiting films – offering on Friday, 7 July, an old favourite, Mary Pickford in Poor Little Rich Girl (US: Artcraft, 1917). Although they didn’t advertise the fact in the newspapers, other cinemas seem also to have opened that day. “Business as usual was the position of Dublin yesterday outside a comparatively few buildings damaged or wrecked in the area of the late fight,” the Irish Independent reported on 8 July. “Most of the city cinema have resumed business, but the theatres are still closed […] due to the absence of the necessary arrangements with artistes” (“Conditions Back to Normal”).

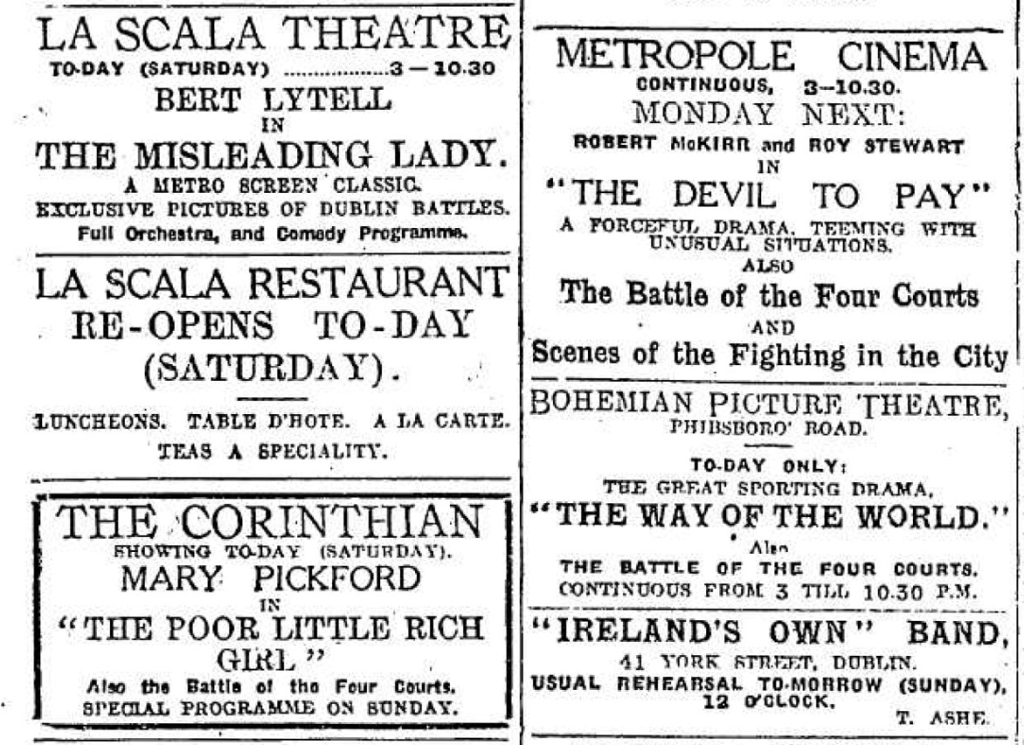

If the Corinthian’s first ad didn’t mention newsreel, the following day’s entertainment ads indicated that several city cinemas, including the Corinthian, were already showing or intended showing film of the Battle of Dublin. The Evening Herald’s entertainment columns on 8 July had ads for four cinemas – La Scala, the Corinthian, the Metropole and the Bohemian – all of which mentioned footage of the fighting. The Metropole seems not to have been open on that Saturday but advertised its Monday programme as including The Battle of the Four Courts and Scenes of the Fighting in the City, if the latter was an actual film title. The other three cinemas were open, the Corinthian and Bohemian including The Battle of the Four Courts on that day’s bill and La Scala promising “exclusive pictures of Dublin battles.”

What is worth noting here is that the rewitnessing involved a recirculation of newsreels that were a week old. The first newsreels of the conflict had been released the previous Monday, 3 July, when the three major newsreel series – Pathé Gazette, Topical Budget and Gaumont Graphic – all featured items focusing on events at the Four Courts. But as usual, a newsreel issue covered several stories. On 6 July, the Kinematograph Weekly delivered the “Hot News” that

the “Pathé Gazette,” number 890, released on July 3, included realistic pictures of the battle of the Four Courts in Dublin, and some right up to the moment shots of the world’s tennis championships taken from the air, together with pictures of ex-President Taft and the Lord Chancellor receiving honorary degrees at Oxford University.

The Kine Weekly also praised Gaumont’s work, noting that London-based newspapers had used images from the previous week’s newsreel to illustrate stories of fighting in Dublin. “This Monday,” it observed, “the ‘Graphic’ scored again with pictures of the destruction of the Four Courts. The cameraman, J. Silver, actually secured the pictures under fire” (“Gaumont’s Dublin Battle Pictures”).

The usual run of a newsreel issue was three days, so these must have been the ones that JHC had noted on 5 July. On 3 July, the Battle of the Four Courts had itself occurred three to six days previously and the fighting was then on O’Connell Street. On 10 July, therefore this was almost two-week old news. JHC had put a subheading “These Can Wait” in his column dealing with the 3-5 July newsreels. “The public was suffering these attractions first hand,” s/he opined. “Everybody knew that the cinema could hardly improve on the pulsing nowness of the real article. For the moment the Dublin point of view is not, as one might say, bioscopic. Film foot-notes to history will have their vogue – later on.”

It took only a week, it seems, for the Dublin point of view to become bioscopic. By the week of 10 July, the city’s cinemagoers had perhaps had enough of the pulsing nowness of the real and were ready for history’s film footnotes. Or that as JHC argued on 12 July, that

thumping realities go best on the screen. The events of the past fortnight fulfil Lessing’s exacting definition of drama – “life with the dull parts left out.”

Of course the moralists are right. It isn’t good for us that our lives should be too picturesque and interesting. Happy the people whose annals are vacant.

Those who had been on the wrong end of the thumping reality of artillery fire and sniping in the city would no doubt have agreed that it was a good thing that the conflict was now safely contained on the screen, at least for the moment.

The prominence of newsreels in Dublin cinemas in the first half of the week beginning 10 July is largely attributable to J. Gordon Lewis, the camera operator who became Pathé’s main representative in Ireland after the indigenous newsreel Irish Events wound up at the end of 1920. Despite the skill under fire of operators such as Silver working for other companies and what Ciara Chambers has called Topical Budget’s exceptional “comprehensiveness in its coverage of Irish affairs,” Lewis’s local knowledge allowed him to successfully time the release of a Pathé compilation newsreel to catch the public mood (Chambers 119). “I have met scarcely one Dublin picture-goer who did not anticipate with interest the cinematographic record of recent events,” the Freeman’s “Cinema Notes” columnist revealed. “And to-day we are getting it in the Pathe Gazette – a big film, made from three series of the Gazette joined into one. It is certainly a marvel of cinema photography; and even more to those who can appreciate the details than to the layman.”

Those in the trade did indeed take notice of Lewis’s work, not least a writer in the Kine Weekly whose account of Lewis’s heroic filming offers details of the film not recorded elsewhere, helping us to reconstruct what he presented on 10-12 July. This writer claims that “last Monday, four numbers of the Pathé Gazette were released in Dublin, giving to the people of the city Mr. Lewis’s record of Dublin’s latest agony.” Although the newspaper ads mention merely battles and fighting, the film also contained other material, beginning with “the last pilgrimage of all the Republican leaders to Wolfe Tone’s grave, with close-ups of each.” This is undoubtedly the film Pilgrims after the Poll, shot on 20 June and prepared for release on 29 June. The writer also mentions material that is more readily identified with the surviving Pathé footage, including close shots of the setting on fire of the Gresham Hotel in O’Connell Street, troops distributing bread to women and children, smoke-filled streets in which an officer is seen firing between two armoured cars and the bombardment of O’Connell Street’s iconic Hammam Hotel.

“Every aspect of Dublin’s battles have been recorded somehow by Gordon Lewis, Pathe’s intrepid photographer of the Irish portion of the Gazette,” the Freeman writer concluded, “little details in the series Dublin is to see to-day prove their absolute under-fire authenticity.” It was Lewis, it seems, who allowed the city’s cinemagoer a fearful joy in rewitnessing the Battle of Dublin.

References

“Awe-Stricken Crowd: The Damage on the West Side of O’Connell Street.” Evening Herald 6 Jul. 1922: 1.

Chambers, Ciara. Ireland in the Newsreels. Dublin: Irish Academic P, 2012.

“Cinema Notes.” Freeman’s Journal 10 Jul. 1922: 3.

“Cinema Notes.” Irish Times 15 Jul. 1922: 7.

“Conditions Back to Normal: Dublin Enjoys Peace.” Irish Independent 8 Jul. 1922: 6.

Dorney, John. “Today in Irish History, 28 June 1922, the First Day of the Irish Civil War.” 28 June 2017. The Irish Story <https://www.theirishstory.com/2017/06/28/today-in-irish-history-28-june-1922-the-first-day-of-the-irish-civil-war/#.Yt0wSITMJEZ> . Accessed 24 Jul. 2022.

“Dublin’s Bill: Cost of Recent Destruction: £244,000 Claimed.” Irish Independent 12 Jul. 1922: 5.

“Dublin’s Bill Still Growing: The Havoc of War: Total Exceeds £1,854,000.” Irish Independent 18 Jul 1922: 8.

“Gaumont’s Dublin Battle Pictures.” Kinematograph Weekly 6 Jul. 1922: 67.

“Hot News.” Kinematograph Weekly 6 Jul. 1922: 48.

JHC. “To-Day & Yesterday.” Irish Independent 5 Jul. 1922: 2; 12 Jul. 1922: 4.

“Trade Show Under Fire.” Bioscope 13 Jul. 1922: 27.