Reproduced from the British Newspaper Archive.

In late November 1918, the editorial writer of the British trade journal Bioscope made reference to Sinn Féin, Ireland’s radical independence party, while warning cinema proprietors against involvement in the upcoming “khaki” election – so named because mass demobilization of military personnel had only begun and many voters remained in uniform. “Confound Their Politics!” the article’s main title read – meaning the policies of all political parties – while the subtitle suggested that the trade should remain focused on a result favourable to “Screen Fein: For the Cinema Alone.” The article noted the inevitability that “the moving picture, whose power as an agency for propaganda has been amply demonstrated in the war, would quickly be wooed as a new electioneering instrument by the existing party organisations.” But the writer argued that these parties should be treated warily by the trade: cinema should be politically unaligned.

An Illustrated London News photograph of the first meeting of Dáil Éireann; reproduced from Century Ireland.

Nevertheless, the writer chose to make a bilingual punning reference to Sinn Féin, albeit s/he did feel it necessary to remind his/her reader of how to translate it. The writer didn’t mention Irish politics any more explicitly in the course of the article: Irish politics was both familiar enough to serve as the basis of a pun and fraught enough to be beyond further consideration. Nevertheless, Screen Fein is too suggestive a term not to be reappropriated from this context in which it received little attention. Among its many more contemporary resonances is the recent rebranding of the Irish Film Board as Screen Ireland, which in the longstanding naming practice of Irish public institutions are known by the bilingual titles Bord Scannán na hÉireann/Irish Film Board and now Fís Éireann/Screen Ireland. But it might be more appropriate to repurpose Screen Fein for the intensely political Irish context of late 1918 and early 1919 that saw the electoral triumph of Sinn Féin. Did an Irish screen culture exist that responded to or participated in these events? That is, of course, one of the questions that this blog as a whole attempts to address, and it would consequently answer “yes” and add “but it’s complicated.” An illustration of both the yes and some of its complications can be seen if we focus on cinema’s role in one important historical moment that has received considerable attention a century later: the founding in Dublin on 21 January 1919 of Dáil Éireann, the independent parliament of an Irish republic.

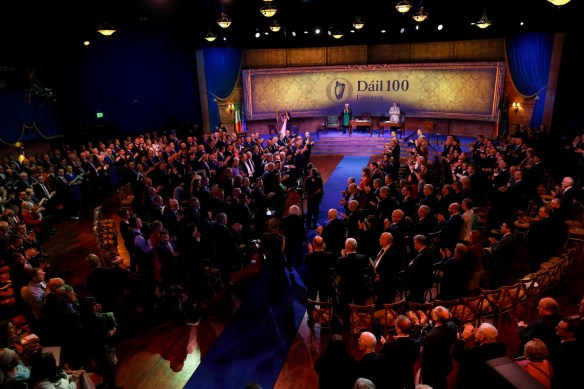

President Michael D Higgins arrives at Dublin’s Mansion House to deliver a keynote address to both house of the Oireachtas on the occasion of the centenary of the first Dáil. Image: president.ie.

In a televised event on 21 January 2019, President of Ireland, Michael D. Higgins, led speeches to a joint session of the Oireachtas at Dublin’s Mansion House to mark the centenary of the first sitting of Dáil Éireann. Film cameras had also captured the proceedings at the Mansion House a century earlier, when 27 of the members of the Sinn Féin party who had been elected in the December 1918 general election fulfilled their electoral promise by not going to the British parliament in Westminster and instead constituting the parliament of the Irish Republic that had been declared at Easter 1916.

Screenshot of the British Universities Film and Video Council’s record of Topical Budget’s issue on 27 January 1919, featuring Sinn Fein Parliament as item #3.

One of the five items on Topical Budget’s newsreel released on the Monday following events at the Mansion House was the Sinn Fein Parliament, “the first newsreel to report the establishment of the Dáil” (Chambers 89). Topical Budget may have been the first of the British newsreel companies to show these events, but the Irish Events newsreel appeared on the same day as Topical Budget and gave them far greater prominence. As one film among five, this Topical Budget’s item would have run about a minute in the middle of four other one-minute items. By contrast, for Norman Whitten, proprietor of the Dublin-based General Film Supply company that produced Irish Events, the developments at the Mansion House were not only the most important events of the week but so important that he devoted the full issue of Irish Events to them. Unfortunately, despite its acute historical interest, the film of the first Dáil – in either its Topical Budget or Irish Events form – does not survive to illuminate that historical moment. Nevertheless, in 1919, many people from all over Ireland unable to attend the Mansion House watched the Irish Events version of what had occurred. While they would already have been well informed by the extensive newspaper accounts, in watching the film, they became the kind of mediated eyewitnesses to events that only moving pictures could have facilitated.

The cover of the May 1918 issue of Irish Limelight carried an ad for Irish Events that listed some of its subscribers around the country. Image courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.

The Irish Events newsreel of the first Dáil was shown as the weekly edition of Irish Events beginning on Monday, 27 January. It would have been seen by patrons at the cinemas all over Ireland that subscribed to this newsreel. How many cinemas exactly this was in January 1919 is not clear; an ad in the December 1917 issue of the Irish Limelight had put the number of subscribed exhibitors at 50, and a May 1918 ad in the same publication had named 35 premises in 27 Irish cities and towns that offered it. “I would be almost safe in saying,” the Bioscope’s Irish correspondent Paddy speculated in September 1918, “that there is hardly a theatre left in Ireland which does not show it.” This was an exaggeration, but it is likely true that the number of subscribers had at least remained at a high proportion of Irish cinema from when Paddy had made that remark, in the week that the 60th weekly edition of Irish Events (IE 60) had just been released to the release of the first Dáil film as Irish Events no. 81 (IE 81).

This ad for IE 57 is unusual in the detail it provides about the content of this newsreel focused on one of the country’s biggest horse races, the Galway Plate. Dublin Evening Mail 16 Aug. 1918: 2.

Although Irish Events had become an expected part of many cinema’s offerings, its content was rarely mentioned after its first few weeks of novelty in July-August 1917. This is because like the British newsreels Gaumont Graphic, Topical Budget and Pathé Gazette that were also regularly shown in Irish cinemas, it was a five-minute digest of five one-minute social and political news stories that formed part of a two-hour programme headed by a fiction feature. Nevertheless, Irish Events was distinguished from the British newsreels in that its contents were at least occasionally mentioned in ads and notices. On Saturday, 29 June 1918, for example, Dublin’s evening papers named two of the items that were to appear in the following Monday’s edition of Irish Events (IE 51): the Irish Derby and the annual republican pilgrimage to Wolfe Tone’s grave at Bodenstown. A month and a half later, many newspaper ads revealed that IE 57 consisted of just one item: a film of the Galway Plate horse race. “It clearly depicts the entire race through from start to finish,” an ad for Dublin’s Dorset Picture Hall reported, “including the wonderful escapes from death of the various jockeys whose mounts came to grief.”

Ad for Dublin’s Rotunda with the Irish Events special Sinn Fein Convention; Dublin Evening Mail 26 Oct. 1918: 2.

IE 57 was unusual in focusing on one story, but it appeared as the regular edition of Irish Events that week. Other special films were issued in addition to the numbered weekly edition, and these had to be advertised to alert exhibitors and audiences to their existence. Whitten had a reputation that predated Irish Events for the “hustle” with which he could shoot, process and print a film in time for exhibition just hours after an event had occurred, and he continued this practice after the introduction of Irish Events. “There was a stop-press edition of ‘Irish Events’ issued last Thursday,” the Irish Limelight commented in November 1917. “The Sinn Fein Convention was filmed at 10.30 a.m. on that day, and screened at a Dublin cinema on the same evening. Some hustle!” (“Stop Press”). Instead of holding over the film of the Sinn Féin convention for IE 16, which would be issued on Monday, 29 October 1917, Whitten rushed the film out on the night of 25 October.

Several Dublin cinemas advertised the Irish Events film of the sinking of the Leinster, Dublin Evening Mail 14 Oct. 1918: 2.

It seem anomalous, then, that Whitten had not rushed out the Dáil special on the evening of 21 January 1919 but had instead held it over for almost a week and issued it as Irish Events’ regular Monday release on 27 January. To a degree this may be explained as an increasing practice of Irish Events over the course of 1918. The Irish Events film of the aftermath of the sinking of the Irish mail boat RMS Leinster appeared as IE 66 on Monday, 14 October 1918, several days after the ship had been torpedoed by a U-boat on 10 October. However, the quite detailed press ads also show that the film remained newsworthy on the Monday of its release because it included footage of the weekend funerals of some of the victims.

Ad for Bohemian Picture Theatre programme featuring the Irish Events newsreel of the first meeting of Dáil Éireann; Dublin Evening Mail 27 Jan. 1919: 2.

This does not seem to have been the case with the film of the Dáil, which looks like it would previously have been seen as a good opportunity for a “stop-press” issue. Much of the information that survives about the film comes from an ad and a brief review of its screenings at the Bohemian Picture Theatre in the Dublin suburb of Phibsboro. The ad reveals that it was indeed an Irish Event special and that it consisted of scenes at the Mansion House, including a group shot of the Sinn Féin members of the Dáil. The review in the Irish Times reported that it was “a special Irish events topical ‘Dail Eireann,’ depicting the principal scenes at the Mansion House on the occasion of the Sinn Fein Assembly” (“Bohemian Picture Theatre”). Little other surviving notice appears to have been taken of the film during the week in which it was on release as IE 81.

Ad offering the film of the sinking of the Leinster to exhibitors who were not Irish Events’ subscribers; Irish Independent 14 October 1918: 2.

Nevertheless, this was unlikely to have been the end of the screening life of this film or of the others Irish Events films mentioned here. As well as releasing his films on the circuit of subscribed cinemas, Whitten also offered then for individual sale, as he did when on 16 October 1918, he placed ads in the Irish Independent for the film of the sinking of the Leinster. Whitten advertised his newsreel specials long after their original newsworthiness had vanished, boasting on one memorable occasion that that his specials “will attract a larger audience than a six-reel exclusive.”

“Behind the Screen” item on “A National Film Library”; Irish Limelight Oct. 1917: 6. Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.

Beyond these commercial afterlives, the newsreels were seen by some commentators as historically important documents. “The successful launching of the Irish News Film ‘Irish Events,’” observed the Irish Limelight’s “Behind the Screen” columnist in October 1917,

has given a fillip to an interesting suggestion made some time back involving the establishment in this country of a Department of Record whose duty it would be to see that nothing of importance happens in any field without being filmed. (“National Film Library.”)

The writer saw the main advantages of such records in writing and learning history but concluded with the intriguing notion that “the establishment of a department such as suggested would secure for future generations the ability to live, as it were, with those who preceded them.”

At a more mundane level, the notion of Irish Events as a repository of Ireland’s history persisted and re-emerged on the occasion of the newsreel’s first birthday in July 1918. “Always a lusty infant,” the “Behind the Screen” writer noted, “it has – during its first year of life – succeeded in accumulating a veritable film library of happenings of intense national importance, the preservation of which were alone well worth while” (“Irish Events”). It is certainly true that Irish Events accumulated a vast amount of newsreel footage on Ireland during what is now being commemorated as the Decade of Centenaries.

However, despite the ability of some contemporary observers to see its importance as historical document, no real vision or infrastructure for preservation existed in the 1910s, nor would they co-exist in Ireland until the founding of the Irish Film Archive (IFA) as part of the Irish Film Centre, now Irish Film Institute (IFI), in 1992. As a result, no more than a few fragments of Irish Events still exists, the vast bulk of which is more than likely lost forever. None of the material so far mentioned in this blog survives – or is known to survive – beyond 30 seconds of the Sinn Fein Convention that remains in the IFA’s Sean Lewis Collection. Working from a roughly calculation that each weekly episode of Irish Events lasted 5 minutes, the newsreel had by the time of the appearance of the special on the first Dáil for IE 81 released 6 hours and 45 minutes of edited footage, and this does not count the stop-press issues that appeared in addition to the regular weekly issues or the two further years of material that appeared after IE 81.

Among this lost material is an important document of Irish feminism, which is mentioned in the January issue of the suffragist Irish Citizen. The paper recorded that in the December 1918 election, the first election after women had won the franchise, “veteran Irish suffragist leader” Anna Haslam

recorded her vote in the midst of an admiring feminine throng to cheer her, was presented with a bouquet in suffrage colours for the occasion, and was snapped by an enterprising film company as one of the “Irish Events” of the Election.” (“Activities.”)

Like the Dáil film, this key moment of Irish social and political history captured in moving pictures exists now only in brief written records.

Despite such great losses, it is heartening to be able to finish this blog by acknowledging that all is not lost, and that 2018 saw the arrival of two particularly useful online resources for Irish cinema history: the IFI’s Irish Independence Film Collection (IIFC) and the British Library’s digitization of the Bioscope. One of the 13 collections of Irish films that are available on the online viewing platform and app IFI Player, IIFC provides access to 139 British Pathé and Topical Budget newsreels items on Ireland from the period 1900-30. Access to these films is not geoblocked; they are readily and freely available through the IFI’s website and app.

A comparison of the quality of the available copies of this 1913 British Pathé film of Jim Larkin shows the undoubtedly better quality of the IIFC copy (right) than the version available on Pathé’s YouTube channel (left).

Some of Pathé’s surviving Irish material has been available on the company’s website and YouTube channel, but IIFC is not just a case of the IFI hosting existing material on its player. For a start, the quality of the new IIFC copies is far better than the material previously available, the result of rescanning the film elements to produce high-definition copies. This increased quality has already revealed and will continue to reveal previously indiscernible details. Although taking the Irish material from Pathé’s website decontextualizes it from that production milieu, historians Lar Joyce and Ciara Chambers provide it with an Irish perspective that is quite different from the British one the newsreels themselves espouse. In the process, they frequently correct misidentifications of people, places and incidents, as well as improper cataloguing for these and other reasons. As the scholar who has done most to analyze the surviving British newsreels’ representation of Ireland through her 2012 book Ireland in the Newsreels and the 2017 television series Éire na Nuachtscannán, Chambers offers particularly incisive commentary on how British newsreels presented a view of events in Ireland favourable to the British establishment.

Comparison of images taken from the newly digitized Bioscope and its microfilmed predecessor; 7 Dec. 1916: 1031.

The different kind of coverage provided by Irish Events during much of the Irish revolutionary decade is not mentioned in IIFC, but it can be glimpsed through the pages of such trade journals as the Bioscope. The most important of British trades for the 1910s, the Bioscope offered significant coverage of Ireland, and it has now been digitized. This has implications not only for searching but also for images, which are barely visible on microfilm but are readily useable from the high-quality scans.

While this is a great improvement on the existing situation, it is not of the standard set by the Media History Digital Library (MHDL), Eric Hoyt’s University of Wisconsin project to digitize media trade journals and fan magazines. While MHDL is a free resource, the digitized Bisocope is only available with a subscription to the British Newspaper Archive (BNA), a digitization partnership between the British Library and the genealogy company findmypast. But by paying the subscription, you do not gain access to a better technology. As well as being free, MDHL allows greater interaction – searching, navigating and downloading – with the scanned volumes than does BNA. For those with a BNA subscription, the two projects can be compared directly because MHDL has digitized a few early1930s’ volumes of the Bioscope that are also part of BNA. Nevertheless, Irish subscribers to BNA also have access to many Irish newspapers, both national and local, that have been and continue to be digitized as part of the project.

Despite some reservations, all of these resources are helping to reveal aspects of Screen Fein, Ireland’s own cinema of a century ago.

References

“Bohemian Picture Theatre.” Irish Times 29 Jan. 1919: 2.

British Newspaper Archive. Find My Past/British Library. www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk

Chambers, Ciara. Ireland in the Newsreels. Irish Academic Press, 2012.

“Confound Their Politics! The Trade’s Election Prospects: ‘Screen Fein’: For the Cinema Alone.” Bioscope 28 Nov. 1918: 4.

“‘Irish Events.’—Many Happy Returns.” Irish Limelight Jul. 1918: 4.

Irish Independence Film Collection. Irish Film Institute, ifiplayer.ie/independencefilms.

“A National Film Library.” Irish Limelight Oct. 1917: 6.

Paddy. “Irish Notes: The General Opinion.” Bioscope 5 Sep. 1918: 91.

“Stop Press.” Irish Limelight Nov. 1917: 13.

Tracy, Tony. “Goodbye Irish Film Board, Hello Screen Ireland.” RTÉ, 23 Nov. 2018, rte.ie/eile/brainstorm/2018/1122/1012662-goodbye-irish-film-board-hello-screen-ireland.