“To facilitate the public who were unable to procure copies [of the Freeman’s Journal],” that newspaper reported on the receipt of news of the Anglo-Irish Treaty on 6 December 1921 in Castlebar, “several traders displayed the FREEMAN’S JOURNAL in the window of their establishments and in addition the management of the Star Cinema threw the substance of the FREEMAN announcement on the screen, acknowledging the source of the information. It was greeted with loud applause” (“Soldier’s Song”). Cinema played a rarely acknowledged role in mediating the Anglo-Irish Treaty, one of the key documents in establishing the constitutional status of Ireland in the aftermath of the War of Independence. While directly projecting text from the newspapers in the way the Freeman described was clearly possible – and we’ll return to that possibility – cinema more often presented the treaty in newsreel images of the negotiations and offered a public space in which people assembled to experience those images together. As the most powerful visual form by which the public saw historic events unfold rather than just reading about them, cinema complemented and to some extent competed with the newspapers, many of whom had over the previous decade or so supplemented its engravings with daily photographs as a way of visually mediating events.

Newspapers were aware of cinema’s increasing presence in the mediascape, and they made the technologically advanced media scrum a newsworthy event in itself, as they did in reports of coverage of the treaty negotiations. “The Irish plenipotentiaries,” the Irish Independent reported on 7 December 1921, “rested most of yesterday in the comparative seclusion of Hans Pl., which was invaded from dawn until nightfall by photographers and cinema operators, endeavouring to snapshot every glimpse of them they could get” (“Arduous Labours”). Indeed, in this case, the Independent mentioned the photographers and newsreel camera operators before the “scores of journalists and special correspondents [who] also besieged the delegates for interviews, but were courteously declined.”

Two other reports in Irish newspapers show that newsreel camera operators were not a rare sight but were seemingly as ubiquitous as other news reporters. As members of Sinn Féin gathered in Dublin on 7 December to begin the debate on the newly signed treaty, the Evening Echo reported that “at 1.50 Mr. De Valera left the Mansion House amid the attention of a number of camera and cinema operators” (“At the Mansion House”). In the immediate aftermath of the treaty negotiations, republican prisoners were released from a number of prison camps and jails, including Dublin’s Kilmainham Gaol, where a “corps of cinema men and press photographers occupied a prominent position outside the building, and interesting pictures of the historic scene were secured” (“At Kilmainham”).

Much of this footage survives and is even familiar from its reuse in historical documentaries. While that reuse tends to decontextualize the footage, we can recontextualize it to some extent with available resources. Camera operators from British Pathé shot a good proportion of the footage of the London negotiations and the Dáil debates that followed from late December 1921 to the Dáil’s ratification vote on 7 January 1922, and what survives can be viewed freely on the British Pathé website. Parts of this footage have been made available in far higher resolution, and also free, on the Irish Film Institute’s IFI Archive Player. Although footage by other newsreel companies – principally Topical Budget and Gaumont – that operated in Ireland is not as accessible, the British Universities Film & Video Council’s News on Screen website offers information on it that indicates the exact date the films were made available and the other newsreel items with which they were shown. Scholars – most notably Ciara Chambers in her Ireland in the Newsreels – have written about the image of Ireland that emerges from these newsreels and offer ways of thinking about the differences between Pathé’s and Topical Budget’s editorial line on Ireland.

As a result, we know quite a lot about newsreels themselves, but we have less information about the cinema context in which people received them. The best-known extant account of an audience watching the footage of the treaty negotiations is fictional. In Ken Loach’s The Wind that Shakes the Barley, the audience in a cinema in rural Cork watches as the terms of the Anglo-Irish Treaty are concisely set out by a newsreel. A pianist accompanies the film, and somebody in the audience reads the text on the intertitles that explain what the main terms of the treaty are. As the concessions made by the Irish side are revealed – “The new state will remain within the British Empire as a dominion.” “Members of the new Parliament will swear an oath of allegiance to the British crown.” “Northern Ireland will remain within the United Kingdom” – the initial celebratory atmosphere changes into one of disbelief and anger. “Is this what we fought for?” Damien O’Donovan, the character played by Cillian Murphy, asks his companions rhetorically.

For Loach, film plays a decisive role in mediating the treaty, and he stages this scene powerfully, capturing the essence of the collective nature of cinema in a film that is so interested in collective decision making and action. Narratively, the scene elegantly and economically communicates the disappointment of those who had been involved locally in the War of Independence by struggling for a better, fairer society in the face of a brutally imposed imperialism. For cinema historians, the recreation of the auditorium’s social interactions and live musical accompaniment lend authenticity that is also present in several other ways, including in the newsreel images on the screen. Among those images, we see footage of Michael Collins giving a speech, the signatures on the treaty document itself, Collins laughing and talking with another man, and King George V and Prime Minister Lloyd George smiling at the front of the British delegation.

Most of this footage derives from “Peace Council at the Palace,” the key newsreel by which people could plausibly have been informed about the treaty. This item was released as part of Topical Budget’s edition of Thursday, 8 December 1921, two days after the treaty was signed. A longer version of “Peace Council at the Palace” also formed part of Pathé Gazette’s edition on the following Monday, 12 December. By that stage, almost a week later, it is unlikely that the film was telling Irish cinemagoers anything they didn’t already know from other sources, and this was the usual situation with newsreel. “Audiences were seldom informed about events via the cinema in the early 1920s,” Chambers observes in a recent article analyzing the use of newsreel in The Wind that Shakes the Barley, “and indeed the newsreels tended to provide moving images depicting events that viewers were already familiar with through newspapers and word of mouth” (“Ethics and the Archive” 140).

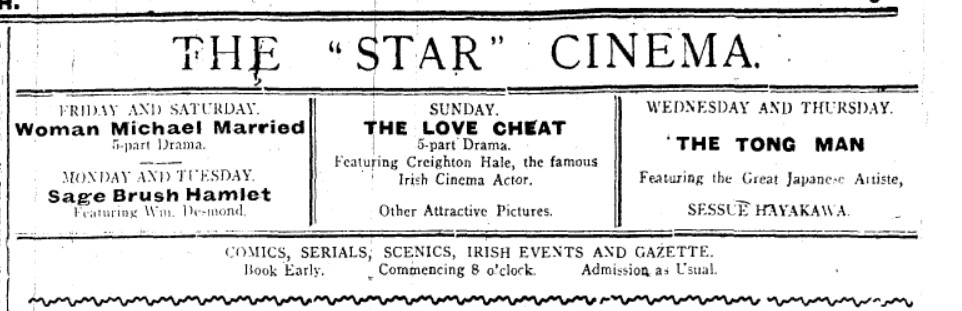

Returning to the Freeman’s Journal article with which we started, it is possible that the 8 December release of the Topical Budget was one of those perhaps few occasions that the cinema informed audiences about an event of which they were unaware, but it is unlikely. The article suggests that copies of the Freeman and possibly the other national dailies were in such short supply in Castlebar that the Star Cinema was needed to help fill the informational vacuum. It doesn’t, however, suggest that newsreel images filled that vacuum but that swiftly prepared text from the Freeman, duly acknowledged, most likely written on magic lantern slides, was projected on the Star’s screen. Although this incident was reported on 8 December, it undoubtedly relates to events on 6 December, the day on which the Freeman had first reported the terms of the treaty. In Castlebar, a town whose population the 1911 census put at 3,698, the scarcity of information would quickly be overcome and was highly unlikely to persist until a newsreel issued two days later. Even if it did, neither of the local cinemas – the Star and Ellison’s – seems to have subscribed to Topical Budget; on the few occasions that their ads mentioned newsreel in 1921, it was with the single word “Gazette,” suggesting they both subscribed to Pathé’s newsreel. Finally, the newsreel was a five-minute compendium of one-minute items of both political and social news that appeared as part of a cinema programme that lasted about two hours. Audiences expected to see this part of the bill, but they were likely at the cinema primarily to enjoy the longer dramatic films that it accompanied.

Having said that, even a single newsreel item could be the cause of conflict between members of an audience, albeit that very little reaction to the treaty newsreel items seems to survive. It doesn’t take long after these items appeared, however, to find an example of how divisive these one-minute films could be, and how the cinema context could display wider societal divisions. “A disturbance between military and civilians broke out last night along The Quay in Waterford, ending in a sharp, short bout of fisticuffs,” the Sunday Independent reported in relation to an incident that took place on 23 December at the city’s Coliseum cinema. “At a cinema performance early in the evening, the picture of Mr de Valera was shown, which was loudly cheered by the audience. These were countered by hootings and groanings on the part of several soldiers attending the performance” (“Civilians and Soldiers”). Which precise film of De Valera was screened is not clear because no Coliseum ads from this period seem to be extant. In any case, it seems that the newsworthiness of the images as such – the fact that De Valera was engaged in the Dáil debates on the treaty and was taking an anti-treaty position – wasn’t an issue for the contending members of the audience but merely provided a pretext to express more general pro- and anti-Sinn Féin positions.

As the article indicates, the incident didn’t end with competing cheers, on one side, and hootings and groanings, on the other. During an interval, some of the soldiers left the cinema to get reinforcements.

The reminder of the performance was marked by disorderly conduct and obscene language on the part of a certain section of the soldiers.

This was resented by the male civilians in the theatre, and later, when the show was over, a body of civilians waited for the soldiers, and on The Quay fighting with fists went on for a considerable time, and the pedestrians feared a general outbreak. (“Civilians and Soldiers.”)

Earlier in the year, a “general outbreak” often meant crown forces going on the rampage, shooting and looting with official sanction for “reprisal.” Here, there seem to be hints of a wider social and political shift in power, with some ominous undertones for things to come. First of all, the article concludes by stating that a full riot, or a breach of the truce that had been in place since July, was avoided when a military patrol arrived to quell the disturbance with fixed bayonets. Up to that point, the article wants to make clear that no firearms were used, but the “body of civilians” who confronted the soldiers on the Quay suggests an intervention by the Volunteers/IRA, an intervention seemingly in the name of a patriarchal respectability given that that it was carried out by “male civilians” who were, the implication presumably is, appalled by the effect on female audience members of the soldiers’ “disorderly conduct and obscene language.”

Cinema was unlikely to have been the place that many Irish people first encountered the details of the treaty. As was usually the case, the daily newspapers scooped the newsreels. However, the cinema provided a communal context in which audiences could respond either to the latest news presented on magic lantern slides or more-or-less delayed newsreel images of the agreement and the people who signed and debated it. That might cause audiences to greet the news with loud applause, hoots of derision or to exchange blows in the street.

References

“Arduous Labours: Irish Delegates’ Work.” Irish Independent 7 Dec. 1921: 6.

“At Kilmainham: Prisoners Stream Out from Early Morning.” Evening Herald 8 Dec 1921: 1.

“At the Mansion House.” Evening Echo 8 Dec. 1921: 4.

Chambers, Ciara. Ireland in the Newsreels. Irish Academic Press, 2012.

—. “Ethics and the Archive: Access Appropriation and Exhibition.” Ethics and Integrity in Visual Research Methods. Edited by Savanah Dodd. Emerald, 2020. 133–151.

“Civilians and Soldiers: Waterford Disturbances Begin in Cinema House.” Sunday Independent 25 Dec. 1921: 1.

“‘The Soldier’s Song’: How the News Was Received in Connacht.” Freeman’s Journal 8 Dec. 1921: 6.