Joseph Holloway spent the last evening of 1916 wandering around Dublin, celebrating the end of a momentous year in Ireland, when he came across a poster for Ireland a Nation (US: Macnamara, 1914). “For a week or more,” the architect and theatre buff observed, “I’ve been reading on the hoardings on a large 15 feet by 9 feet poster bordered with shamrocks – with large ones at angles & printed on green which tells me of the finest picture film ever produced / Ireland a Nation / Nothing like it has been seen before!” (Holloway, 31 Dec. 1916: 1608).

When Waterford-born but New York-based scriptwriter and producer Walter Macnamara had made Ireland a Nation in 1914, the film reflected a very different political situation. Macnamara conceived a film that would trace the history of Irish struggles against British rule from the passing of the Act of Union by the Irish Parliament in 1800 to the passing of the Home Rule bill by Westminster in 1914. He had shot historical scenes – among them the Irish parliament, Robert Emmet’s 1803 rebellion and Daniel O’Connell’s duel with political rival D’Esterre – on location in Ireland and at studios in London, but the film had ended with actuality footage of crowds of Irish nationalists jubilantly welcoming what they thought was the achievement of Home Rule.

The film had been shown in US cities, debuting at New York’s Forty-Fourth Street Theatre on 22 September 1914, but it had not been seen in Ireland (McElravy). The outbreak of World War I had not only caused the suspension of Home Rule, it had also delayed the Irish exhibition of Ireland a Nation. “When Dame Fortune refuses to smile upon a venture, things will somehow manage to go wrong if only out of sheer cussedness,” commented an article in the second issue of Ireland’s first film journal Irish Limelight on the sequence of events that prevented Ireland a Nation reaching the country to date. Two prints of the film sent to Ireland had been lost en route: “[I]t is understood that the first copy dispatched by [the Macnamara Co. of New York] was lost with the ill-fated Lusitania; a duplicate copy was substituted, but as this also failed to successfully run the submarine ‘blockade,’ it became necessary to forward a third” (“Between the Spools”).

These delays meant that it was to a Dublin with many new hoardings erected around buildings destroyed during the Easter Rising that the film returned in late 1916. A large green poster with the slogan “Ireland a Nation” emblazoned on it meant something different in this context. “You read it & wonder when it is to be shown & what is to be the nature of it!” Holloway marvelled. “I have heard it whispered that it is a fake – there’s no such film at all, but those who love Ireland thought that a good way to keep ‘Ireland a Nation’ in the public eye. And the wideawake authorities haven’t tumbled to its purpose!”

A week later, however, a new poster near Holloway’s home on Haddington Road confirmed that this was, in fact, a film by providing more details of the coming exhibition. “I saw on hoarding near Baggot St end of Haddington Rd. that – ‘Ireland a Nation’ for ‘one week only’ was announced for Rotunda commencing Monday next & week,” he noted, “& I thought would we ever have it in reality – for ‘one week only’ even.” (Holloway, 5 Jan. 1917). Holloway’s melancholy reflection related to the distant possibilities for a self-governing Irish nation beyond filmic representation, but even a film of Ireland achieving nationhood would prove impossible to show in January 1917.

Framegrab from Ireland a Nation, preceded by the intertitle: “A New Hope 1914. / A Home Rule Meeting.”

Frederick Sparling was responsible for this poster campaign, after he secured the British and Irish distribution rights to the film in March 1916. The imposition of martial law in the aftermath of the Rising in April made it impossible to screen the film until late in 1916, when Sparling submitted the film to the military press censor (“Irish Film Suppressed”). The censor wrote back to Sparling on 1 December 1916, allowing exhibition if six cuts were made:

-

Scene showing interruption of a hillside Mass by soldiers.

-

Scene showing Sarah Curran roughly handled by soldiers.

-

Scene of execution of Robert Emmet – from entry of soldiers into Emmet’s cell to lead him away.

-

Scene of Home Rule Meeting in 1914.

-

Telegram from Mr. Redmond.

-

Irish Flag displayed at end of the performance.

The following should also be omitted:—from the titles of scenes shown, (in addition to all titles referring to portions of the film which have been censored as above,) “A price of £100 dead or alive on the head of every priest.” (CSORP.)

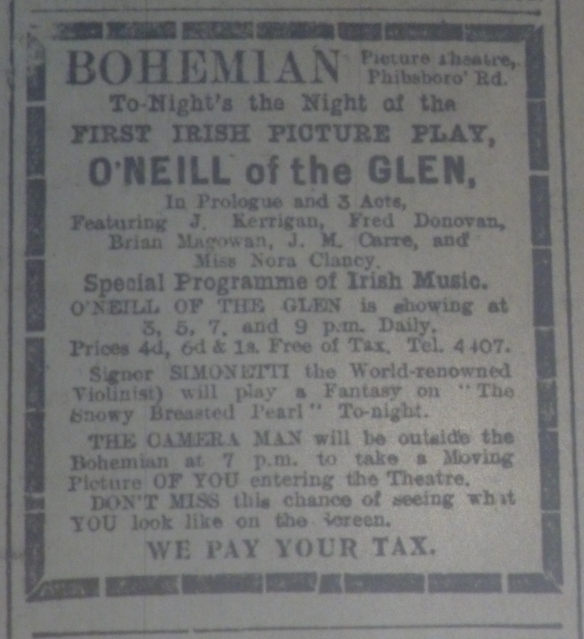

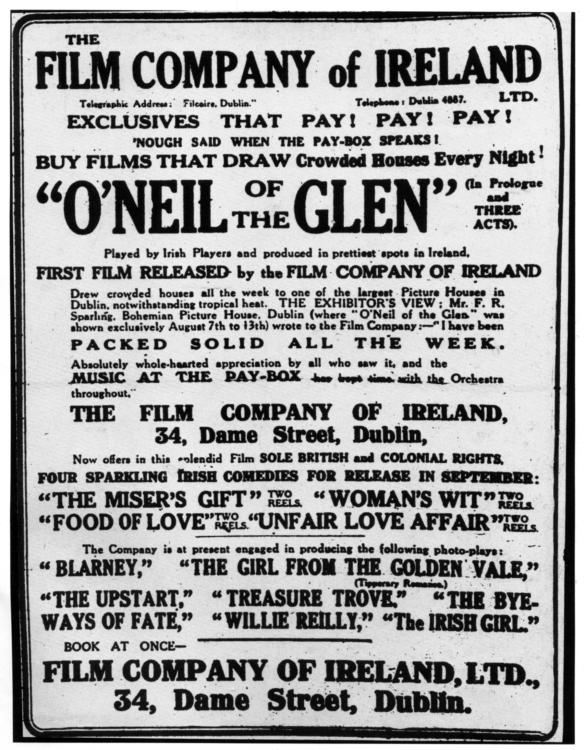

This constituted much of the contentious political material, including the actualities of the Home Rule meeting, but Sparling had no choice but to make the cuts. And although he was the proprietor of the suburban Bohemian Picture Theatre, he hired Dublin’s largest picture house, the city-centre Rotunda, which had a capacity of 1,500 people, a third more than the Bohemian (“Irish Film Suppressed”).

Prominent press ads that followed the poster campaign ensured that potential patrons far and near were well informed of the coming shows. Although the Dublin Evening Mail published these ads, this did not stop a Mr Whitehead from the Daily Express office, which published the Mail, writing to the Chief Secretary’s office, enclosing a copy of the ad and warning that “[i]t is an American Cos film & is of a bad type, indeed, the man in charge of it expresses astonishment that it has passed the British Censor” (CSORP). Inspector George Love of the Dublin Metropolitan Police attended the 2-3pm show on the opening afternoon, Monday, 8 January 1917. Love reported that Sparling had adhered to the censor’s stipulations, but his most interesting comments were those about the effect on the audience:

About 100 persons were present at the opening production and the Picture was received with applause throughout, except some slight hissing, when Lord Castlereagh and Major Sirr were exhibited.

The Films deals mainly with Rebel Leaders and their followers being hunted down by the Forces of the Crown and Informers, and has a tendency to revive and perpetuate, incidents of a character, which I think at the present time are most undesirable and should not be permitted.

While Chief Secretary Edward O’Farrell considered Love’s suggestion that the film be banned by the authorities – and a military observer reported on the opening night to Bryan Mahon, the General Officer Commanding British forces in Ireland – Holloway went to another afternoon screening that had a far larger attendance than the sparse 100 that Love reported at the 2pm show. Indeed, because of the queue at the box office of the ground-floor “area,” Holloway ended up on the balcony. However, the film did not impress him. It reminded him of the increasing repertoire of Irish nationalist history plays by Dion Boucicault, J. W. Whitbread, and P. J. Bourke that had been staples of Dublin’s Queen’s Theatre for decades. Holloway had long been a regular at the Queen’s, but he favoured the kind of restrained acting introduced by the Abbey Theatre. The gestural melodramatic style used by Queen’s actors in the film also contrasted with evolving screen-acting practices. Nevertheless, the film uniquely preserves Irish melodramatic performance of the period.

Other commentators provided more positive reviews than Holloway’s. Perhaps not surprisingly for a nationalist newspaper whose slogan was “Ireland a Nation,” the reviewer in the Freeman’s Journal was enthusiastic, calling the film “[f]rom a historical standpoint, and indeed, from the standpoint of realism, […] undoubtedly excellent” and bound to “attract numerous visitors to the Rotunda during the week” (“Irish History Films”). Although not so wholeheartedly appreciative, the reviewer at the unionist Irish Times confirmed its popularity, noting that “[t]he film, which treated the rebel cause with sympathy, and the music, which included a number of Irish patriotic tunes, were received with loud and frequent applause by the audiences” (“Rotunda Pictures”).

Framegrab from Ireland a Nation, in which Irish revolutionary Robert Emmet (Barry O’Brien) is astonished by the help Napoleon agrees to send for an uprising in Ireland.

Holloway suggested that although the audience was aware of the film’s limitations, it was determined to make the most of this opportunity to celebrate a still imagined Irish nation. “The audience was willing to applaud national sentiments,” he noted, “but was far more impressed by the words card on the screen than by the way the various characters played their parts before the camera.” Indeed, he believed that the film’s title and intertitles carried particular importance. “Truly the man who thought of the title ‘Ireland a Nation’ was worth his weight in gold to the Film Co that produced it,” he argued. “It is the title and not the film drama will attract all patriotic Dublin to the Rotunda during the week.”

Indeed, he was in no doubt that the film did draw unprecedented crowds to the Rotunda. Passing the picture house again later on Monday evening, he recorded:

I rarely saw anything like the crowds that stormed the Rotunda about eight oclock seeking admission. I am sure several thousands were wedged up against the building […]. The night was piercingly cold but the patient waiters kept themselves warm and in good humour by cheering all who left the building & made room for others behind. On the other side of the streets around the Rotunda crowds of people stood looking at the dense black masses clinging on to the walls of the Rotunda like barnacles to the bottom of a ship.

When these later audiences got inside, they were more rowdy than those earlier in the day had been. Love reported that “the Picture was received with applause throughout, except some slight hissing, when Lord Castlereagh and Major Sirr were exhibited” and Holloway that the Irish airs played by the augmented orchestra “were taken up by the audience & sung.” As the evening wore on, audience behaviour grew more explicitly political. “At the last performance of the film on Monday night,” the Bioscope reported, “a large section of the audience sang the song, ‘A Nation Once Again’” (“Irish Film Suppressed”). The military observer advised Bryan Mahon that “the film in question was likely to cause disaffection, owing to the cheering of the crowd at portions of the Film, the hissing of soldiers who appeared in the Film and the cries made by the audience” (CSORP).

As a result, Mahon decided to ban the screenings, but on finding that Sparling had sought and got permission from the military censor, he agreed to try cutting the film further and observe how the Tuesday night screening would be received. “The result of the reports of Tuesday night were more adverse than those of Monday night,” O’Farrell noted, “and in consequence Sir B. Mahon issued an order prohibiting the performance of the Film throughout Ireland, which was served on Mr. Sparling at about 1 o/c on Wed. Afternoon” (CSORP).

The order served to Sparling made clear that the audience’s behaviour caused the prohibition:

The reports received from witnesses, of the affect produced on the audience at the display of the above Film last night, the 9th inst., and the seditious and disloyal conduct apparently caused thereby, make it clear that the further exhibition of the Film in Ireland is likely to cause disaffection to His Majesty, and to prejudice the recruiting of His Majesty’s forces.

I therefore forbid any further exhibition of the said Film in Ireland, and hereby warn you that any further such exhibition will be dealt with under the Defence of the Realm Consolidated Regulations, 1914.

“The Military only allowed Ireland a Nation ‘for two days only,’ at Rotunda,” Holloway lamented. He also pointed out that even the posters did not escape the general prohibition: “In O’Connell Street a man was pasting green sheets of paper on the announcement on the hoarding of IRELAND A NATION. Only a field of green would soon show where Ireland a nation once proclaimed itself.”

Despite the authorities’ efforts to cover over all traces of the film, it continued to be discussed in the following weeks and years. Indeed, Ireland a Nation was and is one of the most significant films of the 1910s in Ireland. In part, this was because its title made it a particular attraction for nationalists at this historical moment, as Holloway suggested, but there are other reasons. Its fascination for nationalists in the aftermath of the Rising made it also of interest to the police and military, who rarely gave much attention to films. As a result, the nature and extent of the surviving sources on the film – particularly Holloway’s diary entries and the official police and military documents – are unusually varied and comprehensive. They allows us to say something about individual screenings of the film in Dublin on 8 January 1917, especially in relation to audience response, which is often the least documented element of an individual film showing.

Ireland a Nation also appeared in Ireland at a significant moment in the press engagement with cinema. The Freeman’s Journal, one of the country’s main daily papers, published an editorial on cinema on 6 January, the Saturday before the film opened. This was not, however, focused on the film, but on the fact that since cinema had taken the place of live theatre, it was “imperative that we should consider how the new theatre can be made subservient to the public utility” (“Cinema”). Nevertheless, with the excitement caused by the release of Ireland a Nation and then its prohibition, cinema had unprecedented visibility on the editorial and news pages of Dublin’s and Ireland’s newspapers well into mid-January.

The debut of the Irish Limelight in January 1917 clearly represented an extremely significant development, not only in its contribution to cinema’s visibility that month but also in its promotion of a more extensive and sophisticated public discourse on cinema over the three years it remained in print. The Limelight was published by Jack Warren, the editor of the Constabulary Gazette, who “for a very long time has taken a serious interest in the cinema world” (Paddy). Because it was a monthly journal, however, the first issue was published before the Ireland a Nation controversy at the Rotunda. The February issue, however, included two significant items on the film: one on its historical inaccuracies and the other – already mentioned – on its ill-fated Irish exhibition. With Warren’s police contacts, the latter could no doubt have provided more insight into the banning than attributing it to the workings of “Dame Fortune.”

As was the case for most of the articles in the Limelight, no author was named for the historical inaccuracies piece, which was instead attributed to a “Student of Irish History” who had sent in a letter in the wake of the banning. Although this correspondent detailed the film’s historical mistakes, s/he nonetheless considered them “too patently ridiculous to call for serious criticisms.” Not that s/he thought the film irredeemably bad, arguing that “the theme was treated by both producer and players with every sympathy and respect, and with a clear eye to propagandism as well as simple picture setting.” Such errors as showing revolutionary priest Fr John Murphy reacting to the 1800 Act of Union when he had been executed in 1798 would have been obvious to any contemporary Irish person with an interest in history. Having pointed out such anachronisms, the writer accounted for them as arising from “a desire to get in prominent figures in the Ireland of the period and weave them into a complete story without any regard for chronological order or historical connection” (“Irish Film Suppressed”).

Erin, the figure of Ireland, inscribes Emmet’s epitaph onto his headstone in Ireland a Nation.

Ireland a Nation argues that the telling of tales is a political act, and that was certainly the case in Ireland in 1917. But this was not the end of the film in Ireland or indeed in America. It was revived – indeed reinvented – first in America and then in Ireland. One of its most vivid storytelling motifs relates to Robert Emmet, who having being condemned to death, famously declared that his grave should be unmarked: “When my country takes her place among the nations of the earth,” he ordered in his famous speech from the dock, “then, and not till then, let my epitaph be written.” In the film, a woman representing Erin, the embodiment of Ireland, inscribes an epitaph onto Emmet’s gravestone because with Home Rule, Irish nationhood had seemingly been achieved. When Ireland a Nation was revived in America in 1920, this material was out of date, and Ireland had not been granted Home Rule. As a result, later newsreel footage of Sinn Féin leader Eamon De Valera’s visiting New York in 1919 to seek recognition of an independent Ireland was added as a further inscribing of the national story. Later again, newsreel of the Irish War of Independence and the funeral of republican hunger striker Terence McSwiney was included.

It was only with the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922 that this film – an incomplete version of which still survives – could be shown in Ireland. The political situation had again changed dramatically in the aftermath of the debates on the Anglo-Irish Treaty by the Dáil (Irish parliament). At least part of Ireland was in some way independent, and one of Dublin’s largest cinemas celebrated by giving an uninterrupted run of Ireland a Nation.

References

“Between the Spools.” Irish Limelight 1:2 (Feb. 1917): 19.

“The Cinema.” Freeman’s Journal 6 Jan. 1917: 4.

CSORP/1919/11025. National Archives of Ireland.

Holloway, Joseph. Holloway Diaries. National Library of Ireland.

“The ‘Ireland a Nation’ Film: Criticisms of Historical Inaccuracies.” Irish Limelight 1:2 (Feb. 1917): 3.

“Irish Film Suppressed: ‘Ireland a Nation’: Military Stop Exhibition at Dublin.” Bioscope 18 Jan. 1917.

“Irish History Films: ‘Ireland a Nation’ at the Rotunda.” Freeman’s Journal 9 Jan. 1917: 3.

McElravy, Robert. “‘Ireland a Nation’: Five-Reel Production Giving Irish History in Picture Form.” Moving Picture World 3 Oct. 1914: 67.

“Rotunda Pictures.” Irish Times 9 Jan. 1917: 3.