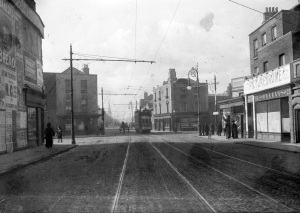

The Pillar Picture House opened on 2 December 1914. This photo shows it in 1921, its distinctive semicircular veranda displaying damage like surrounding building from the fighting of the War of Independence and Civil War. RTE Stills Library; image and discussion here.

Neither weather nor war could seem long to inhibit the progress of Irish cinema in late 1914. “From the cinema man’s point of view this war looks like ‘reel’ business,” announced a one-line item gnomically in Dublin’s Evening Telegraph’s Saturday “Music and the Drama” column, without expanding on any cinematic developments. Nevertheless, this single line seems better to capture developments in popular entertainment in the mid-1910s than the several paragraphs devoted a week later by another columnist in the same newspaper to arguing that “our tastes in amusements and entertainments, indoor and outdoor, run on well-defined lines, and are marked by an extraordinary lack of initiative” (“Notes and Comments”). Drawing on the examples of the ping-pong and roller skating crazes – “the handsome rinks brought very poor prices as scrap” – to show that people prefer “Standard Amusements,” the columnist contended that the “theatre, concert and dance are just the theatres, concerts, and dances of by-gone years with some infinitesimal variations.” “Once or twice in every generation, there are signs of revolt, which are none the less interesting because the innovations have never even a sporting chance of securing a permanent footing” (ibid).

Cinema seems to be left conveniently out of consideration here. Although it had similarities with existing forms of entertainment, it was also significantly different and – as developments in late 1914 showed – was highly successful. Indeed, many of the roller-skating rinks build around the country in the short rinking craze of 1909-11 were not scrapped but had by 1914 become picture houses. Significant capital was also being invested not only in adapting other existing buildings – halls, shops and even churches – but also in constructing new purpose-built picture-houses premises. And building continued five months into the war. As it became part of the Irish streetscape, cinema integrated into the business practices of Irish cities, towns and rural areas; as it became more profitable to be a picture-house proprietor, so it became more socially acceptable to be one. Although doubts about the business stability and the respectability of cinema certainly remained at the end of 1914, it was being reshaped in ways that made it not only acceptable but also ever-more desirable to the dominant business and social class, which was itself changing in the context of the war.

However good its prospects, the cinema business faced challenges. On an elemental level, as a form of entertainment that required people to leave their homes and travel to a picture house, cinema was affected by the weather, particularly extremes of heat or inclement conditions that made travel difficult. Storms of unusual ferocity struck Ireland in the opening week of December 1914. “About midnight last night a violent storm swept over the city,” reported the Evening Telegraph,

bringing about a marked change from the extreme cold that prevailed all yesterday, and that became intensified as the night advanced. A high wind, accompanied by intermittent showers, blew till daylight, when heavy rain fell, and with the gale still fierce, it rained in merciless fashion till after noon, when it developed into a continuous and drenching downpour, which, with violent gusts across the city, made all form of traffic difficult and unpleasant. Dublin has not been visited with such an inclement day for a very considerable time. (“The Weather in Dublin.”)

Hurricane-force winds around the Irish and British coasts severely disrupted shipping, leading to the deaths of 14 men from the steamer Glasgow off the Lizard and 19 of the 250 horses for military use on the Teviot out of Dublin (“Havoc of Hurricane,” “Channel Hurricane,” “Heavy Gale in Dublin”).

Dublin’s Evening Telegraph 2 and 4 Dec. 1914: 2, providing details on opening hours and admission prices at the new Pillar Picture House.

These raging storms had consequences for at least the first of the two cinemas opened in Dublin and Belfast at the start of December and in time for the Christmas season. Although Dublin’s Pillar Picture House opened its doors on that stormy Wednesday, 2 December, it was only formally declared open two days later (“Pillar Picture House”). It was located in the middle of Sackville/O’Connell Street opposite Dublin’s landmark Nelson’s Pillar. At a time of limited personal transport, “the proprietors are especially fortunate in this, as the position is the terminus of all city and suburban trams” (ibid.). The proprietor was the Pillar Picture House Co., headed by John J. Farrell, a prominent member of Dublin Corporation who also had shares in three other Dublin picture houses. The Pillar was managed by Bob O’Russ, who was also managing Farrell’s picture houses in Phibsboro and Mary Street (Paddy, 24 Dec.), and May O’Russ – one of the city’s women musicians who formerly operated the Mary Street Picture House with her husband – directed the Pillar’s orchestra (Paddy, 17 Dec.).

Like many of the city-centre picture houses of the prewar period, the building was small, with a seating capacity of just 400, but it was architecturally striking both inside and out (“The Pillar Picture House, Dublin”). “The façade of the new premises is handsomely proportioned and cleverly treated in modern classic,” commented the Irish Builder, proceeding to detail its attractive features:

The approach is covered with a semi-circular verandah, which follows the sweep of a broad arch, and the opening under is filled in with Sicilian marble and leaded glass. The vestibule is very effectively treated with walnut and satinwood panelling with a fibrous plaster frieze of figured plaques and swagwork. The ceiling is elaborately ornamented and has a semi-circular dome of leaded glass. The staircase to the balcony is also panelled in walnut, and the enclosing walls artistically decorated in fibrous work. (Ibid.)

The overall impression was of “comfort and art combined in a most successful manner,” and commentators also stressed that the work of Irish manufacturers had been preferred (“Pillar Picture House”). “The general contractor was Councillor John Dillon, and the fibrous plaster contractor was Councillor John Ryan. Councillor M‘Guiness was the consulting electrical engineer, and the architect was Mr. Aubrey V. O’Rourke” (ibid.).

Belfast Evening Telegraph 5 Dec. 1914: 2.

The role of city councillors was even more prominent in the considerable publicity that accompanied the opening of Belfast’s Imperial Picture House on 7 December. Before “an exceptionally large attendance of invited guests, including representatives of the Corporation, public Boards, the Church, the legal profession, and the business community,” the Lord Mayor, Councillor Crawford M‘Cullagh “said he was glad to be privileged in his official capacity to be associated in some degree with the progress and business activity of the city,” in this case embodied by “his colleague, Councillor W G. Turner, and his friend, Mr. James Barron, the directors of the Ulster Cinematograph Theatres, Ltd.” (“Imperial Opened”). The opening was filmed and shown as a special feature of the Imperial programme from 11 December.

The invitation-only opening ceremony was extensively covered in the Belfast’s papers and in the Bioscope, which carried a full page article on the Imperial’s architectural features. Prominently located “in that old-world part of the great industrial centre known as Corn Market,” the Bioscope’s Special Representative reported, the Imperial was “[c]onstruucted on the most improved lines [in such a way that] every possible arrangement has been made for the welfare, comfort, and enjoyment of the patrons of the theatre, or of the clientele which the beautifully appointed tearooms is sure to enjoy” (“Ancient and Modern”). Although the writer provided details of the auditorium – particularly such decorative features as the oil-painted panoramas of Belfast above the proscenium – s/he emphasized the the attractions that were not directly connected to watching a film. “A ladies’ retiring room is provided on the mezzanine floor, writing materials, etc., being supplied free of charge. A telephone and cloakroom are provide in the vestibule for the benefit of patrons, and shoppers may have their parcels addressed in care of the hall if they so desire” (ibid). Like a luxury hotel or department store, the Imperial advertised itself as a place where people, particularly the wealthy, would want to linger.

The Imperial maintained a high level of publicity throughout December, publishing more ads than any other form of entertainment. In the Belfast Evening Telegraph, for instance, it published ads not only among the other entertainment ads on page 1 but also on as many of two additional internal pages. As well as this, it advertised and sponsored a benefit on Wednesday, 16 December for the war fund of the lady mayoress, who arranged the participation of local artistes and spent the proceeds on entertaining soldiers who were confined to camp over Christmas (“To Entertain Tommy”).

This kind of publicity strategy was not new but one that the evolving cinema business adapted not only from such longer-established entertainment businesses as theatres but also from business in general, which increased its publicity in the run-up to Christmas, the year’s busiest festival. Despite an expected drop in business during the first Christmas of the war, an extravagance similar to that seen at the Pillar and Imperial seems to have been experienced in the shops. “There are actually areas in the city where more money is being spent than has circulated within living memory,” observed Dublin’s Evening Telegraph. “The crowds are filling the streets. The shopmen are working at high pressure” (“Christmas Eve”)

This title page ad for The Sign of the Cross (US: Famous Players, 1914) at the Bohemian in mid-November 1914 is one of the few picture houses ads that appeared in the Irish-Ireland journal The Leader.

One area of Dublin where more money was being spent on entertainment than ever before was the northern suburb of Phibsboro, where two cinemas had opened in early summer 1914. John J. Farrell’s Phibsboro Picture House had to compete with Frederick Sparling’s Bohemian Picture Theatre. The Bohemian was formidable competition, advertising far more widely than the Phibsboro and introducing such new attractions as the church organ that was installed in November 1914 to accompany the exclusive film The Sign of the Cross (US: Famous Players, 1914). The ability of the Bohemian to secure such desirable exclusive films was, of course, important to maximizing its audience, which for both Phibsboro picture houses meant inducing patrons to travel by tram to this part of the city. The Bohemian also secured the loyalty of its patrons by giving them promotional gifts. While commending Sparling and manager Ernest Matthewson for their choice of Selig’s 9,000-foot adaptation of Rex Beach’s bestselling 1906 novel The Spoilers, Paddy observed that the “Bohemian perfumed calendars and matchbook covers are already well known both to the stern and gentle sex” (Paddy, 24 Dec.).

The war was also “reel” business for picture house managements because it provided a topical subject matter with which to attract audiences. There was a popular understanding the films of the war had a persuasive function, particularly when it was used by the enemy. This was highlighted in early December when the Evening Telegraph’s daily column “Sidelights on the War” published an item called “German Victories on the Cinema,” which reported the alleged experiences of “a gentleman who has been to a biograph show in Germany” and who described “[h]ow the news of fictitious victories is circulated.”

A picture of the Kaiser standing with field-glasses in the trenches (delirious enthusiasm). The picture had to be shown over and over again on a screen a hand writes the latest war news: “An English battleship, believed to be the Warrior, was this morning, near Dover, torpedoed by a German submarine and sank.”

[…]

Next picture: The Crown Prince on horseback. A rather subdued applause follows. On the screen the hand thereupon writes: “A German squadron has this morning reached Ireland; mariners have made a landing in the town – name not permitted by censor.” The audience gets up and sings “Deutschland, Deutschland uber alles.” (“Sidelights on the War.”)

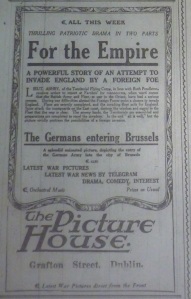

This item clearly implied that the cinema could promote blind devotion to the Kaiser among the German popular audience that generated a war fever that was a danger not only to the sailors of the Warrior but also to Irish citizens facing a German invasion. No similar analysis of Allied war films appeared in mid-December when the Provincial Cinematograph Theatres’ Picture Houses in Dublin’s Grafton Street and Sackville/O’Connell Street and Belfast’s Royal Avenue showed the film With King George in France with The Belgians in Action. Although protests occurred at jingoistic entertainments and criticism appeared in more radical publications, loyalty to King George was accepted by the mainstream Irish press. In late November, the propaganda potential of the war-themed fiction film being produced in increasing numbers by British production companies was highlighted when an ad for one of these films appeared in the Belfast Evening Telegraph below a recruiting ad. While the recruiting ad called for volunteers to the Royal Engineers, the ad for V.C. (Britian: London, 1914), in which a young man dies on a World War I battlefield to vindicate his family’s honour, offered “scenes in the trenches [that] vividly portray modern war conditions.”

The wartime uses of moving pictures were not restricted to their propaganda value in the picture houses. The Bioscope reported comments from the Berlin correspondent of the Spanish El Mundo Cinematografico that “it is evident how much theatrical and cinematographic works can do to lift up and sustain a love of the fatherland in the whole public” (“Cinematography Employed by the Germans”). Citing evidence from the same source on the use of cameras for aerial reconnaissance, the Bioscope argued that “the Germans may claim to be the first nation to put the cinematograph to direct military use in warfare” and urged the War Office and British and French inventors to surpass their enemy (ibid).

By the end of 1914, cinema was showing no signs of going the way of roller skating. It was becoming firmly embedded in the business and entertainment life of Irish cities and towns.

References

“Ancient and Modern: Belfast’s Latest Cinema Described: By Our Special Representative.” Bioscope 10 Dec. 1914: 1143.

“Channel Hurricane: Vessels ‘Sub-Marine’ Passage: Life Boat Lost from ‘Teviot.’” Evening Telegraph 5 Dec. 1914: 4.

“Christmas Eve: Dublin at Its Best: Business Booming.” Evening Telegraph 24 Dec. 1914: 3.

“Cinematography Employed by the German Army: Interesting Details from Berlin of an Alleged New Invention.” Bioscope 10 Dec. 1914: 1076.

“Havoc of Hurricane: Horses Killed on Board Ship: Steamers Forced Back to Dublin: Vessels Blown Down the Liffey: Sailings Postponed and Cancelled.” Evening Telegraph 4 Dec. 1914: 3.

“Heavy Gale in Dublin.” Irish Times 5 Dec. 1914: 5.

“The Imperial Opened: Belfast’s Palatial Picture House: A Civic Ceremony: Home of Pleasure and Comfort.” Belfast Evening Telegraph 9 Dec. 1914: 2.

“Music and the Drama.” Evening Telegraph 5 Dec. 1914: 6.

“Notes and Comments: Standard Amusements.” Evening Telegraph 11 Dec. 1914: 2.

Paddy. “Pictures in Ireland.” Bioscope 17 Dec. 1914: 1217; 24 Dec. 1914: 1347.

“Pillar Picture House.” Evening Telegraph 5 Dec. 1914: 6.

“The Pillar Picture House, Dublin.” Irish Builder 27 Feb. 1915: 98.

“Sidelights on the War: German Victories on the Cinema.” Evening Telegraph 7 Dec. 1914: 2.

“To Entertain Tommy.” Belfast Evening Telegraph 17 Dec. 1914: 5.

“The Weather in Dublin.” Evening Telegraph 2 Dec. 1914: 2.