Reporting on their work in the final quarter of 1913, the Dublin Corporation councillors on the Public Health Committee revealed that they had granted an application for a pay increase made by two public servants. Building surveyors J.J. Higginbotham and William Mulhall deserved an extra £15 per annum because

the duties of examining plans of proposed Places of Public Resort, and the inspection and charge of the several Theatres, Cinema Houses, and other Places of Public Resort, had, to a large extent, devolved to them. […] There had been a large increase in the number of places of public amusement within recent years. These were scattered over a large area, and required frequent inspection to ensure the observance of the Regulations” (Dublin Corporation).

In 1910, the Corporation had increased the pay of Walter Butler, inspector of theatres and places of public resort, in acknowledgement that his work had increased with the introduction of the 1909 Cinematograph Act. However, with the growth in the number of picture houses and their wider distribution around the city than any other places of public resort, Butler delegated more of that work to Higginbotham and Mulhall, and they had to be compensated for the extra workload in their turn. Although the most obvious manifestation of the popularity of cinema was the appearance of a new kind of building on the streetscape, among many less apparent but wide-reaching material effects was its contribution to the careers of certain public officials.

Building regulation was one of the ways that cinema became a cultural institution imbedded in the institutional landscape of 1910s Ireland, and it raises questions about who was doing the regulating. This process was driven from inside Dublin Corporation and other local councils by powerful councillors and other senior officials who were sometimes themselves picture house proprietors or shareholders. John J. Farrell – Dublin’s mayor in 1911 and proprietor in 1913 of the Electric Theatre, Talbot Street and Mary Street Picture House – is frequently cited in this regard (Rockett 28-9, 33-4). However, Farrell was by no means alone in his conflict of interest. Dublin’s long-serving chief medical officer Sir Charles Cameron performed the opening ceremonies of several picture houses, including such early ones as the Dublin Cinematograph Theatre – later the Picture House, Lower Sackville/O’Connell Street – in April 1910, and Farrell’s Electric Theatre in May 1911. When he opened the picture house at the Clontarf Town Hall in July 1913 – receiving a gift of a gold-mounted umbrella – he revealed that he was a shareholder in a cinema company “which was paying 20 per cent., and he was only sorry he didn’t sell out all he had and invest the proceeds in a picture house (applause and laughter)” (“Clontarf Electric Theatre”).

Dorset Picture Hall, in its later guise of the Plaza, clearly retaining its origins as a Baptist chapel. (Irish Architecture Online.)

Twenty percent was also the handsome return on profit enjoyed by Farrell and the shareholders of the Talbot Street Electric Theatre, but Cameron was not among these shareholders; “he only honoured us by opening it” (“Dublin Electric Theatre”). Nevertheless, Farrell appealed the Electric’s £160 valuation in November 1913, and the Recorder (chief magistrate) reduced it, accepting that the Electric should not have a higher valuation than the Dorset Street Picture House, which Farrell claimed could hold 1,600 people and charged 3d, 6d and 1s when the Electric had to do away with the top rate on its 3d-6d-9d scale. Effectively shifting attention onto the Dorset, whose owner had no known links to the Corporation, Farrell observed that “in Lent, when other places of a like character were nearly empty, the door porter at Dorset street held out his hands and said, ‘Room for no more’ (laughter)” (ibid).

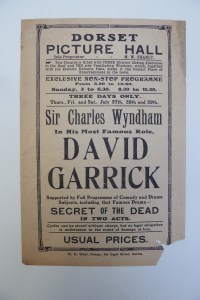

Handbill for M. W. Shanly’s Dorset Picture Hall in July 1914, featuring the latest film adaption of T. W. Robertson’s play David Garrick. (Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.)

Indeed, the Dorset was an interesting venue; one of the largest picture houses in Dublin, it had been barely converted from the former Bathesda Chapel by M. William Shanly, who was known primarily for providing chairs at parks in London and Dublin (“Dorset Picture Hall”). Despite having a much larger capacity than the Electric, it resembled Farrell’s picture house in housing a tearooms and being located well off the city centre’s main thoroughfares and close to a large railway station; in the Dorset’s case, this was Broadstone Station. “Travellers can see the pictures, and have their tea, with the assurance that they have not far to go when the time comes to catch their train” (Paddy, 14 Mar. 1912). Already an imposing building, the Dorset was by night “a veritable blaze of light. No less than 300 electric lamps adorn the building, and they have been grouped with care” (Paddy, 5 Dec 1912). Although many patrons smoked, “improved ventilators on the sides and roof of the hall, and on the stage [ensured that] there are scarcely any smoke rays form the operating box to the screen” (ibid).

With such a large clientele, the Dorset required an extensive staff, and Shanly and his manager Frederick William Sullivan advertised for many of these positions in the Irish Times in March 1911. These included ticket checkers, bill posters, a lady pianist who could play to pictures, two young women to sell tickets and refreshments, an experienced assistant operator to help with the picture house’s five projectors, and boys to sell programmes. The requirements for the door porter mentioned by Farrell were most specific: the two men who were sought must have retired from the police, present a smart appearance, be active and be prepared to wear a uniform. Shanly and Sullivan clearly intended to give the impression that whatever the state of picture houses in other parts of the city, the behaviour on their premises would be well regulated.

Not all Irish picture shows in late 1913 had an imposing attendant or two on the door capable of deterring unruly behaviour. On 22 November, the small County Dublin town of Balbriggan witnessed scenes of uproar, when a group of six local young men rushed the Town Hall to gain free admittance to a picture show (“At the Cinema”). Rather than a burly ex-policeman on the door, a man named McInerney “constituted himself doorman at the outer entrance on the occasion, and was trying to keep order, in the hope that his efforts in that direction might be rewarded by free admission to the pictures” (ibid). McInerney was no match for the six young men, some of whom

went into the passage where tickets for the cinema performances were being issued, and by their frightful language and disorderly and violent conduct caused such a scene of confusion that many intending patrons of the show turned away from the door, while other, who were already inside, came out again through fear and went home (ibid).

At the trial of the young men for riotous and disorderly behaviour, local lamplighter Patrick Darkin “informed the magistrates that there was ‘a terrible lot of pups in Balbriggan,’ and advised their Worships to put a stop to their conduct, which, he said, had resulted in a great deal of damage to the Town Hall” (ibid). Effective regulation of picture houses would be necessary for the cinema to considered respectable entertainment. This would serve the business interests of owners and shareholders, including those working within Dublin Corporation to ensure that their own business interests were legally protected.

References

“At the Cinema: Wild Scenes in Balbriggan.” Evening Telegraph 3 Dec. 1913: 6.

“Clontarf Electric Theatre: New Picture Enterprise.” Freeman’s Journal 19 July 1913: 5.

“Dorset Picture Hall.” Irish Builder 13 May 1911: 317.

Dublin Corporation. Committee Minutes, 1914: 1, pp. 592-3.

“Dublin Electric Theatre: Appeal Against Valuation of Premises.” Dublin Evening Mail 4 Nov. 1913: 3.

Paddy. “Pictures in Ireland.” Bioscope 14 Mar. 1912: 759.

Paddy. “Pictures in Ireland.” Bioscope 5 Dec. 1912: 725.

Rockett, Kevin and Emer. Film Exhibition and Distribution in Ireland, 1909-2010. Dublin: Four Courts, 2011.