July 1914 began with a heat wave in Ireland, and although temperatures fluctuated thereafter, political developments nationally and internationally grew increasingly heated up to the August bank holiday. “Tuesday’s sunshine was the hottest on record this year,” commented Dublin’s Evening Telegraph on Wednesday, 1 July.

From its rising to its setting the sun blazed in a cloudless sky. Ninety-six degrees were registered in the city, and in many parts of the country the thermometer rose to over 100 degrees in the sun. Monday, too, was intensely hot, registering 76 degrees in the shade. Dublin would seem to have been transferred to the tropics. (“The Heat Wave.”)

For such indoor entertainments as cinema, summer weather that allowed outdoor activities was bad news. “To successfully compete with the open-air attractions,” revealed a review of the Phoenix on Dublin’s Ellis Quay, “a big bid is being made by the Phoenix management (“Phoenix Picture Palace,”11 Jul.). As well as the right films, this picture house boasted about its comfortable environment. “The Phoenix is most comfortable this hot weather, for, besides being a big, airy house, it is supplied with electric fans that change the air constantly, and keep it delightfully cool” (“Phoenix Picture Palace,” 30 Jun). This kind of discussion was by no means exclusive to Dublin. The British trade journal Bioscope’s “Jottings from Ulster” columnist observed that “[a]t this time of year especially, temperature should receive as much attention as the programme” (“Jottings,” 9 Jul).

How the auditorium could be made bearable during even ordinary summer weather was a controversial subject. “The advent of the hot weather is always heralded by the revival of that interminable controversy dealing with ventilation,” noted the Bioscope. “Every cinema boasts of having a more or less “perfect” system of ventilation – a term which is so tentative as to mean almost anything” (“Trade Topics” 9 Jul). Although the Phoenix appears to have invested in a relative sophisticated air-conditioning system, it is not clear how the management of Dublin’s Volta kept it “well ventilated and cool” (“The ‘Volta’ Sunday Pictures”). It’s possible the Volta used the more cost-effective but unpopular strategy of having a cinema attendant spray a scent in the air above audience members – many of whom in 1914 had infrequent access to bathing facilities – as they sat watching the screen in the heat of an otherwise unventilated auditorium.

Handbill for opening of the Masterpiece Theatre, featuring the film Joan of Arc; Joseph Holloway Diaries, National Library of Ireland.

Despite their sometimes inability to deal with climatic conditions, new picture houses continued to open regularly in the immediate pre-war period. Following the openings of the Phibsboro Picture House and Bohemian Picture Theatre in late May and early June, the next picture house to open in Dublin was the Masterpiece Theatre at 99 Talbot Street. Owned by Charles McEvoy – “a gentleman with a good experience of the producing end of the business in Australia” (Paddy, 6 Aug.) – and designed by architect George L. O’Connor, it had “no gallery, so that the flow of air passes through the theatre uninterrupted” (“Masterpiece Picture Theatre”). The 450 patrons who fitted inside approached the picture house through an entrance that was

quite the finest in Dublin. The pay-box is on the right, and having passed through white doors set with stained glass, one traverses a short space of tiled flooring leading up to three steps. The steps surmounted and rich velvet curtains passed, one finds oneself in a form of lounge, beautifully decorated with framed photos of the leading picture play artistes. On either side of the lounge are long forms richly upholstered in Rose Barri tinted velvet. A sweet and cigarette kiosk stands at the left. (Paddy, 6 Aug.)

On either side of the screen were boxes for “the person who explains a particular picture or sings when pictures adapted to this use are thrown on the screen” (“Masterpiece Picture Theatre”) All seats were 6d., and performances were continuous from 1.30 to 10.30. The opening programme was headed by Joan of Arc (Giovanna d’Arco; Italy: Savoia, 1913), supported by “‘Relaying a Railway,’ ‘A Wise Old Dog’ (comic), Topical Topics (cartoons), and ‘Just Kids’ (Comedy)” (ibid).

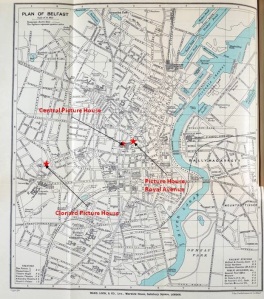

The opening of the Masterpiece was accompanied by the founding of other new Irish cinema companies. On Dublin’s Sackville/O’Connell Street, J. J. Farrell was building what would be called the Pillar Picture House on part of the site formerly occupied by a pharmacy, while on the other part of this site “a notice has just been put up to the effect that Irish National Picture Palaces, Limited, have secured the site, and will shortly open a theatre capable of holding 1,200” (Paddy, 16 Jul.). Picture houses were also under construction in Dublin’s Manor Street, in Kilkenny, in Coleraine and in Newry. In Belfast and other parts of the north, the increasingly armed resistance of the Ulster Volunteers to Home Rule was no barrier to the local film business. “Despite the trouble now brewing in Ulster,” Jottings observed, “cinematograph theatres are springing up here, there and everywhere. Permanent buildings, too, for the days of the temporary halls are well on the wane in the Northern province of Ireland to-day” (Jottings).

Detail of Dublin Civic Exhibition’s Concert Hall and Cinema, from Evening Telegraph 14 Jul. 1914: 1.

“I really do not know where the building of additional theatres in Dublin is going to stop,” marvelled Paddy, the Bioscope’s Irish correspondent, at the end of July, after a 600-seat temporary concert hall and cinema opened for the Dublin Civic Exhibition, which ran from 15 July to 31 August 1914. “At the Civic Exhibition the cinema theatre is, without the slightest doubt, one of the most popular sideshows” (Paddy, 30 Jul.). Erected on the site of the city’s Linenhall, the Civic Exhibition, aimed

to produce a considered plan, so as to show how Dublin can be made a better commercial and industrial centre, and how, with improved conditions (which will be illustrated by the various section and exhibits) the trade, manufactures, and commerce of the city must increase in a large degree.” (“Dublin Civic Exhibition,” Jul)

As with all such world’s fairs, the latest entertainments were vital not only to amuse audiences but also as a manifestation of the benefits of industrial progress. The appointing of vocalist John C. Browner as manager of the Exhibition’s concert and cinema hall rather than someone with picture-house experience seems to have been a deliberate strategy to promote the educative potential of the medium. In keeping with the theme of the exhibition, the most advertised “cinema” attraction was the Kinemacolor films that were combined with lantern slides of the National Cash Register Company of Dayton, Ohio, in order to illustrate “Industrial Welfare and Commercial Progress,” the free daily lecture about this model factory. The film programme was not always so dull. When Bibian Foran visited the Exhibition from Listowel, Co. Kerry, she noted that thousands of children who were admitted free were rewarded for their patience in having the exhibits explained to them when they were treated to a film show. “[N]ot the least happy memory,” she remarked, “is associated with the delighted ripple of laughter which greeted the humorous pictures given for their entertainment or the ‘Nation Once Again’ sung by hundreds of small voices when leaving the Exhibition two by two and in perfect order” (“Dublin Civic Exhibition,” Sep).

The Lord Lieutenant patronized the Princess in Rathmines to see the film of the opening of Dublin Civic Exhibition; Evening Telegraph 18 Jul. 1914: 1. Ad for illustrated lecture in the Exhibition’s Cinema Hall; Irish Times16 Jul. 1914: 9.

Although the Civic Exhibition did not reproduce the kind of commercial cinema that was thriving in the city beyond its grounds, it was the subject of a film shown in Dublin’s picture houses. “The Lord Lieutenant was present at the Princess Cinema, Rathmines, on Saturday afternoon,” reported the Irish Times,

when a picture of the opening of the Civic Exhibition was exhibited. By arrangement with the Exhibition Committee, the picture was produced by the management of the Princess Cinema. Eight cinematograph operators, under the direction of Mr. James Worth, were stationed at various points on the route of the procession and at the Linen-hall. The result of their work is highly creditable. (“Dublin Civic Exhibition: Lecture on Dublin Housing.”)

Despite the commercial cinema’s exclusion from the exhibition itself, such high-profile screenings demonstrated the mutual benefits to the industry and dominant social class of cinema’s increasing absorption into Ireland’s mainstream media. Among the messages of this film was that despite the recent defeat of workers during the Lockout, the elite were engaged in tackling such problems as the appalling housing condition – and indeed homelessness – of the city’s poor. The Irish Times’s Clubman reported that Harvard professor of social ethics James Ford had told a conference convened as part of the exhibition that a city “in which a large section of the population lived in such a monstrous way as the 51,000 families are housed in Dublin was doomed to decay” (“Dublin Topics”). Although such analysis was important, it was also largely contained by the organization and media framing of the exhibition. Arguably more unsettling in the picture houses was the anarchic humour of Charlie Chaplin’s tramp character in such films as The Film Johnnie (US: Keystone, 1914), which was shown at the Rotunda on 21 July. The tramp provided working-class audiences with ways of seeing “their anger and frustrations recognized, transformed, and liberated” (Musser, 62).

The entertainment ads in the Evening Telegraph on 30 Jul 1914 included a film of the funeral of the Bachelors Walk shootings at the Rotunda.

The cohesive social structure seemingly on show in the Civic Exhibition film was less in evidence after the Howth gunrunning on Sunday, 26 July, and the shooting dead by soldiers later that day of three people on Bachelors Walk. Following the Ulster Volunteer Force’s highly successful gunrunning at Larne in April 1914, the Irish Volunteers finally succeeded in landing and distributing arms at Howth in defiance of the police supported by a military detachment. Soldiers returning to barracks responded with bullets to the taunting of a crowd in the city centre. The Irish Times described the public funeral of those killed as an “impressive spectacle” that had been “made the occasion of a popular demonstration by the various elements of Nationalist forces, and, besides being an indication of sympathy with the relatives of those who were killed, it was chiefly intended as a protest against the action of the military” (“Dublin Shooting Affray”). Among the groups who turned out was a large contingent of the workers’ “Citizen Army, headed by Mr. James Larkin” (ibid). No footage was taken of the landing of the weapons, but the funeral was filmed. Among the film companies that covered the funeral was Norman Whitten’s General Film Supply, which shot part of their Funeral of Victims Shooting Affair Sunday, July 26th from the Bohemian Picture Theatre in Phibsboro (Paddy, Aug. 6).

Although the struggle for and against Home Rule had dominated Irish politics for decades, the outbreak of the Great War would complete change the country and its fledgling ciinema institution. As a harbinger of those changes, the Bioscope’s 6 August issue announced the first of a different kind of local film taken on 2 August that would set the tone for coming events: “The first local picture in connection with the war was taken in Glasgow on Sunday evening, when Messrs. Green’s Film Service secured a fine film of the Naval Reserve entraining en route for Portsmouth” (“Trade Topics,” 6 Aug). Capturing the initial patriotic war euphoria that cinema would help to foster, the article noted that “[t]he picture was shown in many halls in Monday, and was received with great enthusiasm.”

References

“The Champion Fight Pictures.” Evening Telegraph 11 Jul. 1914: 7.

“The Civic Exhibition.” Evening Telegraph 9 Jul. 1914: 7.

“Dublin Civic Exhibition: The Attraction for All Parts of the Country.” Irish Times 4 Jul. 1914: 7.

“Dublin Civic Exhibition: Lecture on Dublin Housing.” Irish Times 20 Jul. 1914: 10.

“Dublin Civic Exhibition: An Active and Leading Participator from North Kerry Interviewed.” Liberator 26 Sep. 1914: 6.

“Dublin Shooting Affray: The Funeral.” Irish Times 30 Jul. 1914: 7.

“Dublin Topics by the Clubman: City Housing.” Weekly Irish Times 1 Aug. 1914: 4.

“The Heat Wave: Yesterday Hottest Day of Year.” Evening Telegraph 1 Jul. 1914: 3.

“Jottings from Ulster.” Bioscope 9 Jul. 1914: 138.

“Masterpiece Picture Theatre.” Irish Times 28 Jul. 1914: 3.

Musser, Charles. “Work, Ideology, and Chaplin’s Tramp.” Resisting Images: Essays on Cinema and History. Eds. Robert Sklar and Charles Musser. Philadelphia: Temple UP, 1990.

Paddy. “Pictures in Ireland.” Bioscope 16 Jul. 1914: 253; 30 Jul. 1914: 494; 6 Aug. 1914: 545.

“Phoenix Picture Palace.” Evening Telegraph 30 Jun. 1914: 3; 11 Jul. 1914: 3; 18 Jul 1914: 2.

“Trade Topics.” Bioscope 9 Jul. 1914: 113; 6 Aug. 1914: 532.

“The ‘Volta’ Sunday Pictures.” Evening Telegraph 11 Jul. 1914: 3.