“Some people when they want to be amused go to a theatre, a circus, or the Kinemac,” explained a writer in the Southern Star in October 1915. This newspaper primarily addressed a readership in the environs of Skibbereen, Co. Cork, for whom the Kinemac, the local entertainment hall, was the place where “[a]s a rule they get the full value of their money in laughter, hearty or otherwise” (“Skibbereen and Carbery Notes”). Indeed, in Skibbereen, the Kinemac appeared for a time to be synonymous with popular entertainment and particularly moving pictures. For instance, when in March 1915, Jeremiah McCarthy – leading stoker of HMS Devonshire – related his war experiences in the battles of Heligoland Bight and Dogger Bank, the seriousness of these contrasted with his demeanour while in Skibbereen, where he was described as being “as cheery and light-hearted as a small boy going for the first time to the Kinemac” (“Skibbereen Man in North Sea Battles”). Similarly, when The O’Donovan – chief of an Irish sept and colonel in the Munster Fusiliers – addressed a recruiting meeting in the west Cork town of Ballydehob in May 1915, he told his hearers that it was necessary to give a graphic account of German brutality in Belgium, which he said had been particularly expressed in the rape of Belgian women:

The man who lives out in the country, though he may see the films occasionally at the Kinemac, does not realise these things, nor appreciate the horrors that would happen his own country, his wife and daughters, and his sisters if the Germans ever invade Ireland, as they may, if not driven back in Flanders and France. (“Ballydehob Meeting.”)

So, although the word “Kinemac” does not echo down cinema history, these references give an indication of the degree to which this picture house had become embedded in the entertainment culture of west Cork in 1915. That might seem of limited local interest, but the story of the Kinemac has national and international aspects unique in early Irish cinema. It was built by a local man with money he had made selling his mechanical vibrators to the world; it was founded in order to provide funding for the paramilitary Irish Volunteers; and it was a financial failure.

Financial failure was some way off when on 14 December 1914, the Kinemac was opened with much ceremony by Henry O’Shea, mayor of Cork city, for the proprietor, Gerald J. Macaura (“The ‘Kinemac’”). O’Shea’s attendance was an acknowledgement of Macaura’s support for the Skibbereen Volunteers and the Irish Parliamentary Party. When the Skibbereen Volunteers were founded earlier in 1914, Macaura had donated £50 in cash, and he had – seemingly on an impulse of his own– bought a set of silver-plated instruments for the establishment of a Volunteer band in the town. He built the Kinemac in order to provide a continuing source of funds for the training of local boys by J. G. Chipchase, a bandmaster he had brought from England. Even before the Kinemac opening, Macaura’s munificence had been rewarded with the title of honorary colonel of the Volunteers.

Part of the patent document for Macaura’s “movement cure apparatus,” dated 23 Dec. 1902.

Such munificence was possible because “Colonel” Macaura was more internationally famous – and eventually notorious – as “Dr” Macaura. Dr Macaura was the inventor and popularizer of the Pulsocon, a handheld vibrator. Born Gerald McCarthy in Skibbereen, the son of a master cooper and Fenian activist, Macaura emigrated to the United States where he had relatives in construction (“Death of Dr. Gerald J. Macaura”). His obituary repeated the claim that he had worked with Edison, but this seems to be as spurious as his medical education. Both a professional connection with the most prominent inventor of the age and the letters “Dr” or “Prof” before one’s name were part of a formula for a lucrative career in quackery. In 1898, “Professor” Macaura demonstrated to the people of Skibbereen and of Cork city that he also possessed the indispensable quality of showmanship, when he treated them to a demonstration of his prowess in hypnosis (“Hypnotic Seance”). Returning again in 1901, having “pursued his course of studies in the Sheerin Psychological College, Columbia, Ohio, [and having had] conferred on him the degree of Doctor,” he held a fundraising entertainment with Edison’s latest phonograph in aid of the Skibbereen Temperance Hall (“Entertainment in Skibbereen”). And in December 1902, Macaura patented a device in the United States that would provide the basis of his fortune. Beginning life as the somewhat prosaically titled “movement cure apparatus,” this would later become popular as the more colourful “Oscilectron,” “Pulsocaura,” and – most famously – “Pulsocon.”

Macaura’s career with the Pulsocon was an international one, but aspects of it can be seen in the way he operated in Ireland. In 1911, he held lavishly advertised demonstrations of the device in Dublin and Cork presenting himself as “Dr. G. J. Macaura, F.R.S.A., of the National Medical University, Chicago.” The Dublin demonstration was held at the Theatre Royal, the city’s largest theatre, on 13 April, an event whose lack of an entry fee ensured a very full house. Following this public launch, he offered to consult with sufferers from ailments ranging from rheumatism to deafness at his Institute at 16 D’Olier Street in the city centre. The Institute remained in operation with frequently ads until 17 June, when Macaura moved his show to Cork, where he used the same publicity techniques and public meeting – in this case, at the Assembly Rooms on 15 August – before establishing an Institute there until 20 September. The Pulsocon show did not come to so small a town as Skibbereen, but the money Macaura earned from these lucrative shows funded his exploits there.

Interest in the Pulsocon continues, particularly as part of a hidden sexual history of the early 20th century; these images are from here, here and here.

When he hit on the idea of the Kinemac in late 1914, therefore, Macaura was a self-made man, used to success and overcoming such occupational hazards as his prosecution for fraud and the illegal practice of medicine in France between 1912 and 1914 (“Dr Macaura Arrested,” “American ‘Medicine Man’”). As a mark of that success, the returned cooper’s son bought Lough Ine House near Skibbereen and began disbursing funds as an entry into Irish nationalist politics. As Macaura’s largess grew, the local papers were careful to assert his lack of political ambition. “Although not a politician,” the Cork County Eagle observed when the Kinemac was first announced in October 1914,

Dr. Macaura is very keen on the Volunteer movement. He speaks highly of Mr. John Redmond’s services to Ireland, and it is under his leadership that Dr. Macaura has bestowed these gifts on the movement. When the Hall, which will be a costly structure, is completed. Dr. Macaura’s contributions to the local Volunteer fund will amount to close on £1,000.” (“Skibbereen National Volunteers.”)

Nevertheless, despite the fact that his business was based in London, Macaura returned to Skibbereen at strategic intervals.

He was not, however, intending to manage the Kinemac himself and seems to have expected that his Skibbereen ventures would become self-running and self-funding. The Kinemac was to be operated by a committee associated with the Volunteers, and Macaura expected it to provide a profit that would cover the band’s expenses. As somebody involved in a branch of show business in the United States and Europe, Macaura had undoubtedly seen the money that could be made from picture houses. But he does not seem to have considered whether or not a town with as small a population as Skibbereen could sustain a full-time picture house. Something has already been said here about a population in the region of 5,000 being needed to make a picture house financially viable in the mid-1910s. Skibbereen’s population of just 3,021 in the 1911 census made it likely that a full-time picture house would struggle to earn a profit. And it did.

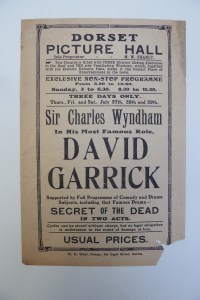

Initially, the Kinemac resembled many picture houses across Ireland. It offered a nightly show beginning at 8pm, changed the programme on Mondays and Thursdays and charged 3d., 6d. and 1s. admission. It could accommodate 209 patrons on 119 tip-up seats in brown leather cloth, 68 tip-ups in green plush, and 22 leather-covered seats (“Kinemac, Skibbereen”). It offered a programme of dramatic, humorous and travel pictures, including special war films, with such attractions as The Sign of the Cross (US: Famous Players, 1914) receiving special publicity in early March 1915.

Despite such spectacles, the Kinemac was already failing to meet its running costs six months after it opened when it ran into political controversy because of its links to the Volunteers and their band. Following the recruiting drive by The O’Donovan and others, 22 Skibbereen men left the town to join the 9th Battalion of the Munster Fusiliers on 10 June 1915 “amidst a scene of great enthusiasm” (“Volunteers’ Departure”). However, the recruits were played onto the train not by Macaura’s Volunteer Silver Band but by the band of the Baltimore Fishery School because the Volunteer Band committee, led by Councillor Timothy Sheehy, refused permission for them to play. The reasons for this are not clear, but it could be that Sheehy and other members of the committee had not agreed with John Redmond’s policy on the National Volunteers entering the British Army. This is suggested by a mock-heroic ballad in the Cork County Eagle commemorating these events, which observed of Sheehy that “There never was a public thing / That he had not on hand, sir, / Except recruiting against the Huns, / For which he refused the Band, sir” (Simple).

At the end of June 1915, Macaura returned to Skibbereen and had a handbill distributed calling the townspeople to a meeting in the square so that he could explain his disagreement with this decision on the use of the band and the financial difficulties faced by the Kinemac (“Clearing the Air,” “Skibbereen Band Crux”). This was an extraordinary move to undermine his local opponents, and the public meeting was a forum in which he excelled. As the ballad said of Macaura’s actions,

He built this Hall for Picture Shows,

And called it the ‘Kinemac,’ sir,

Gave its control to a Committee,

To which now he has give the sack, sir;

That Kinemac has changed its name

And is known as the ‘Picturedrome,’ sir;

And Michael John is Agent now,

And Manager – one Macowan, sir.” (Simple.)

Suggesting that the committee was biased against the town’s Protestants, who had in turn boycotted the Kinemac, Macaura removed the committee and replaced them with his agent Michael J. Hayes. He closed the Kinemac for the summer months and arranged that it would be run in the autumn by Alex McEwan, the well-known proprietor of Cork city’s Assembly Rooms Picturedrome. And on 10 July, the Macaura Silver Band gave a send-off to five Skibbereen recruits (“Send-Off to Skibbereen Recruits”).

Ad for the auction of the Kinemac’s furnishings and building materials. Cork County Eagle 4 Aug. 1917: 4.

However, the Kinemac did not prosper, even under a professional picture-house manager. In part, this may be attributed to a lasting and perhaps not unearned ill will towards Macaura. When he attempted to get his cinematograph licence changed into McEwan’s name by Skibbereen Urban Council, Sheehy complained that Macaura had taken back a gift he had given to the Volunteers in the presence of the Lord Mayor of Cork. McEwan did, nevertheless, run the Kinemac in late 1915, but did not return for a second season. In his stead, Southern Coliseums – which ran the Coliseum and Tivoli in Cork city and which among its other venues, opened a Coliseum in Waterford in October 1915 – reopened the Kinemac as the Coliseum, Skibbereen, on 25 April 1916, the day after the Easter Rising had begun in Dublin. Again, the picture house failed to attract enough patronage, with a local columnist commenting in September 1916 that “it is a pity that the Coliseum was not patronised better since its re-opening [following a summer hiatus] a fortnight ago, but the meagerness of the attendance each night may be attributed to the exceptionally fine weather” (“Local and Other Newsy Items”). Whatever the reasons for poor attendance, Macaura eventually cut his losses on the Kinemac and sold it all – from furnishings to structural timbers – for scrap in August 1917.

The story of the Kinemac is more than just a curious case of a failed picture house at a time when cinema was on the ascendant. It throws unusual light on the motivations of those who built these venues. While this is probably the only case in which a vibrator salesman built a picture house to fund a nationalist band, it exposes the importance of considering a broad constellation local circumstances when assessing the reasons why a picture house succeeded or failed.

References

“American ‘Medicine Man’ Sentenced as Swindler.” Freeman’s Journal 15 May 1914: 9.

“Ballydehob Meeting.” Skibbereen Eagle 29 May 1915: 10.

“Clearing the Air: Colonel Macaura Puts a Plain Issue Before Skibbereen People.” Cork County Eagle 26 Jun. 1915: 11.

“Death of Dr. Gerald J. Macaura: Skibbereen Loses Distinguished Son: Worked with Edison.” Southern Star 10 May 1941: 3.

“Dr Macaura Arrested.” Freeman’s Journal 25 May 1912: 4.

“Entertainment in Skibbereen by Professor Gerald J. Macaura.” Southern Star 5 Oct. 1901: 5.

“A Hypnotic Seance.” Cork Examiner 27 and 29 Aug. 1898: 1; Southern Star 30 Jul. 1898: 1.

“The ‘Kinemac’: Opening Ceremony at Skibbereen.” Southern Star19 Dec. 1914; 1.

“The Kinemac, Skibbbereen: Important to Builders and Others.” Ad. Cork County Eagle 4 Aug. 1917: 4.

“Local and Other Newsy Items.” Cork County Eagle 23 Sep. 1916: 7.

“Macaura Volunteer Silver Band: Concert at the Kinemac.” Cork County Eagle 20 Mar. 1915: 9.

“Send-Off to Skibbereen Recruits.” Cork County Eagle 10 Jul. 1915: 12.

Simple, William. “Skibbereen.” Cork County Eagle 14 Aug. 1915: 9.

“Skibbereen and Carbery Notes.” Southern Star 9 Oct. 1915: 9.

“Skibbereen Band Crux: Dr. Macaura Comes from London.” Southern Star 26 Jun. 1915: 5.

“A Skibbereen Man in North Sea Battles.” Cork County Eagle 6 Mar. 1915: 9.

“Skibbereen National Volunteers: Dr. Macaura’s Munificence.” Cork County Eagle 3 Oct. 1914: 4.

“Volunteers’ Departure.” Southern Star 12 Jun. 1915: 5.